2002.602.1 / The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Right: Headdress depicting a mosquito. Alexander Archipelago (Alaska), 1844

571-20 / Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (Kunstkammer), Saint Petersburg

A hero takes revenge on a man-eating ogre for the murder of his older brothers. He burns the body of the ogre on a pyre and scatters the ashes—its particles transform into mosquitoes. That is why their bite is painful: they are what is left of that ogre. Thus the genesis of mosquitoes is explained in a storystoryNora Marks Dauenhauer, Richard Dauenhauer Haa shuká, our ancestors: Tlingit oral narratives. Classics of Tlingit oral literature vol. 1. (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1987). recorded in July 1971 in Angoon (Alaska) as told by Robert Zuboff (Shaadaax'Shaadaax'Tlingit name of the storyteller Robert Zuboff, meaning “on the mountain” or “around the mountain.”

), one of the Tlingits, people native to the Northwestern coast of North America. In one of the texts put togetherput togetherJohn Reed Swanton, Tlingit Myths and Texts, Recorded by John R. Swanton (Washington: Govt. print. off., 1909).

by the American anthropologist, folklorist, and linguist John Swanton in 1904 in Wrangell, Alaska, the mythological demiurge Raven burns the body of Wolverine. The bones in the pyre ask to be pulverized and scattered. Turning into mosquitoes, they stay in this world forever and continue to torture Raven himself, as well as all other living things. The Tlingit tradition has a rather large number of texts about killing Mosquito, who even after his own death continues to cause human beings trouble.

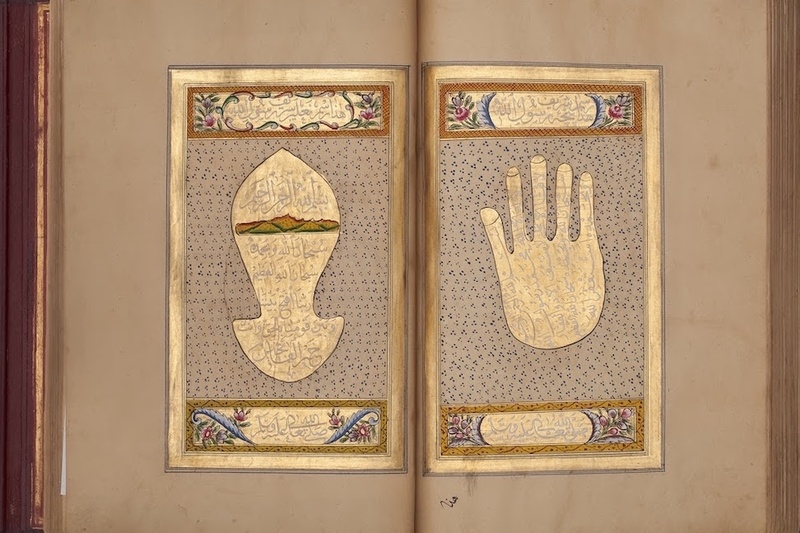

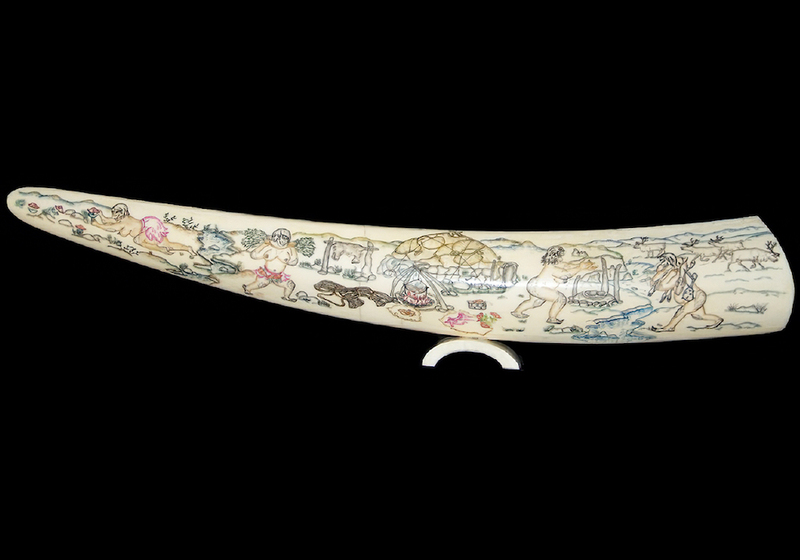

The image of the mosquito was frequently usedfrequently usedSteven Brown. Spirits of the Water: Native Art Collected on Expeditions to Alaska and British Columbia, 1774-1910 (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2000). by the Tlingits when making masks and headdresses. These were worn by chiefs during important processions accompanying peacemaking and during festive ceremonies. They were used in funerary rites. Headdresses also played a part in dancing rituals, which were theatrical reenactments of myths. Masks could moreover depict helpful spirits—not necessarily mosquitos—which inhabited shamans so that the latter could carry out their rituals. Many Tlingit beliefs and rites were related to living creatures and fantastical elements were added to their depictions. For example, two practically identical headdresses with toothed mosquitoes have survived to this day. One of them is in the collection of the St. Petersburg Kunstkammer, while the second is stored in the vaults of the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art.

6981 / National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution

Right: Mosquito mask with removable proboscis. Alexander Archipelago, Alaska, 19th century

2448-13 / Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (Kunstkammer), Saint Petersburg

The first headdress ended up in St. Petersburg due to an expedition led by Ilya Voznesensky. In 1839 he was sent to the Russian colonies in America to gather zoological and botanical collections. Voznesensky was a commoner; he studied specimen preparation at the Zoological museum and he did not have to be paid much. The congress of the Academy of Sciences decided to use this opportunity and tasked Voznesensky with acquiring materials for the collections of the Kunstkammer Ethnographical Museum of the Petersburg Academy of Sciences as well, for which he received a separate set of instructions.

After eight months at sea, Voznesensky arrived at Sitka island (now officially called Baranof island) in the Southeast of Alaska. In the course of the following four years, moving all across the coast, he gathered hundreds of cultural artifacts belonging to the native inhabitants of Alaska, Kamchatka, and Northern California, among them clothes, weapons, tools, whole boats and, of course, masks and headdresses, including that very same mosquito headdress. All this he described and sent to Petersburg with the ships of the Russian-American company. Voznesensky bought and exchanged most of these objects from merchants, officials, and missionaries; sometimes he received them as gifts. This makes his part of the Kustkammer collections stand in a more favorable light in relation to the items that we can learn from the catalogue may have belonged to the natives whose settlement was burned by the first governor of Russian America, Alexander Andreyevich Baranof—the very same man whose name Sitka island now bears.

The American headdress surfaced at the very end of the 1990s at a small auction in New York, where it was acquired rather cheaply by the private collector and scientist Ralph T. Coe. The seller took the artifact to be a modern replica—a copy of a shaman mask from the Northwestern coast of America. But Coe pointed out that despite a slight difference in size and preservation of detail (one headdress retained feathers and baleen hairs, while the other had a fragment of a bristle and copper eyebrows), the two objects belonged to a pair. The state of the objects, signs of wear, the age of the paint, and their similarity all point to the fact. Where the second headdress had been for all those years and why Voznesensky did not purchase both of them straight away remains a mystery.

Translated from Russian by Diana Khamis

Drawing by Ilya Voznesensky. Shaman rite among the Tlingits. Sitka Island (Alaska), 1842

1142-32 / Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (Kunstkammer), Saint Petersburg

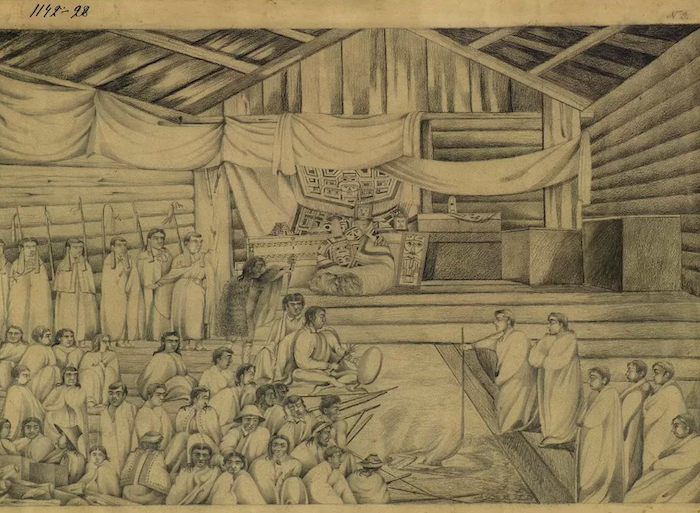

Drawing by Ilya Voznesensky. The funeral of the Kolosh toion, the Thin-Armed (Kukhan-Tan), taking place inside the communal house. Sitka Island (Alaska), 1844

1142-28 / Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (Kunstkammer), Saint Petersburg

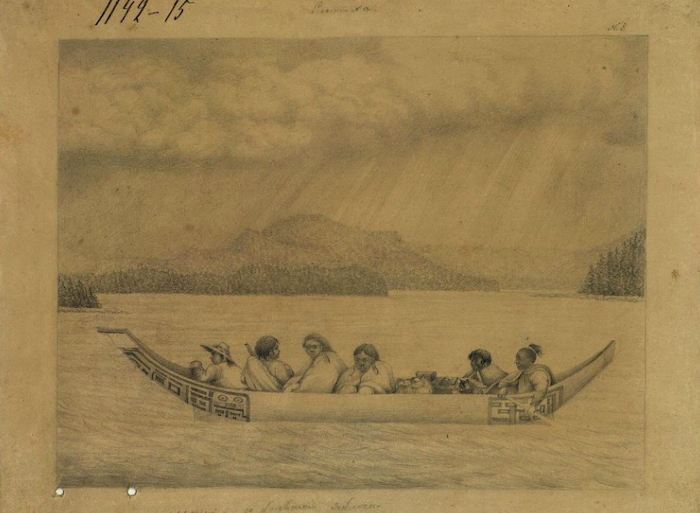

Drawing by Ilya Voznesensky. Sitka: Little and Big Iablochnye Islands, 1844 год

1142-15 / Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (Kunstkammer), Saint Petersburg

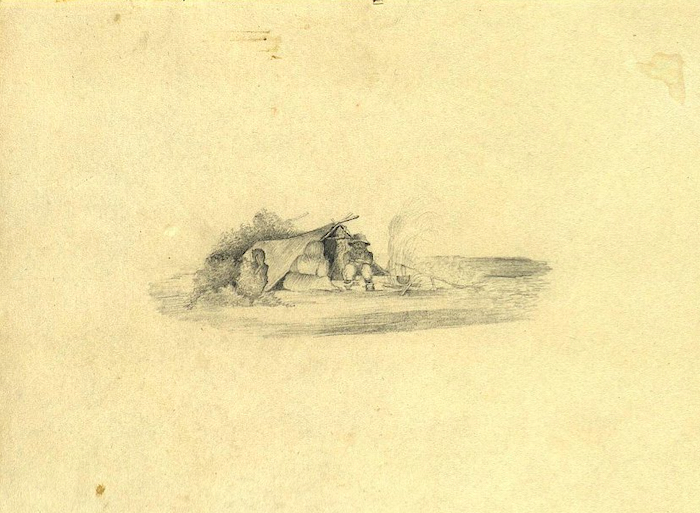

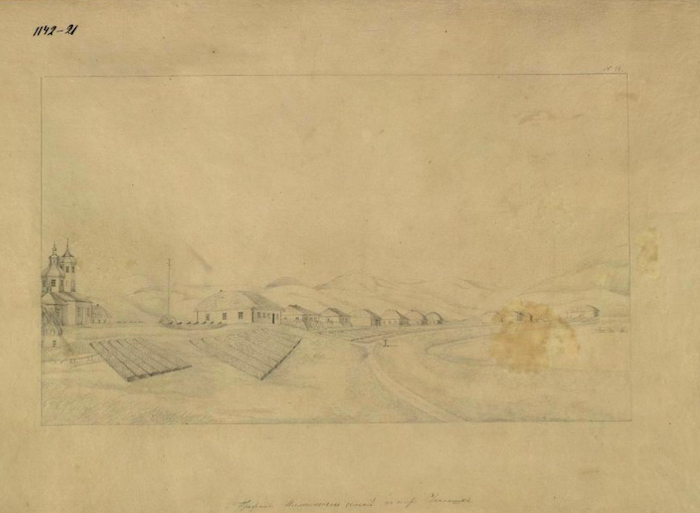

Drawing by Ilya Voznesensky. The RAK [Russian-American Company] Post in Aian Bay, 1845–1846

1142-15 / Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (Kunstkammer), Saint Petersburg

Drawing by Ilya Voznesensky. A European colonist. Western Pacific Coast, 1841 год

1142-4/4 / Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (Kunstkammer), Saint Petersburg

Drawing by Ilya Voznesensky. A view of Illiuliuk settlement on Unalaska Island, 1843

1142-9 / Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (Kunstkammer), Saint Petersburg

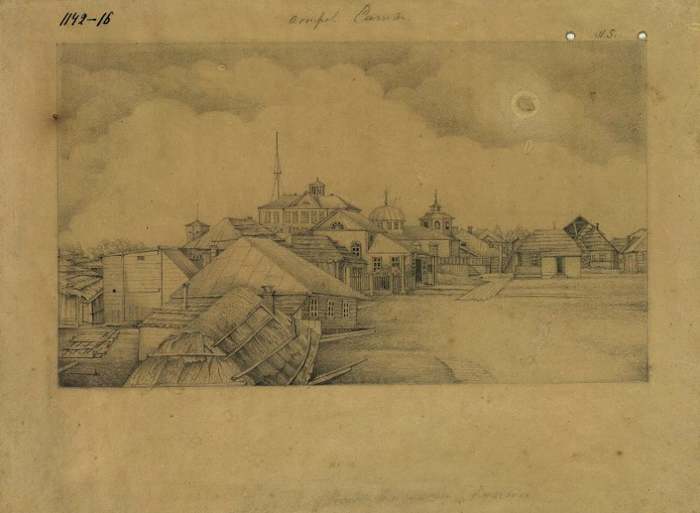

Drawing by Ilya Voznesensky. Sitka Island, 1844

1142-16 / Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (Kunstkammer), Saint Petersburg

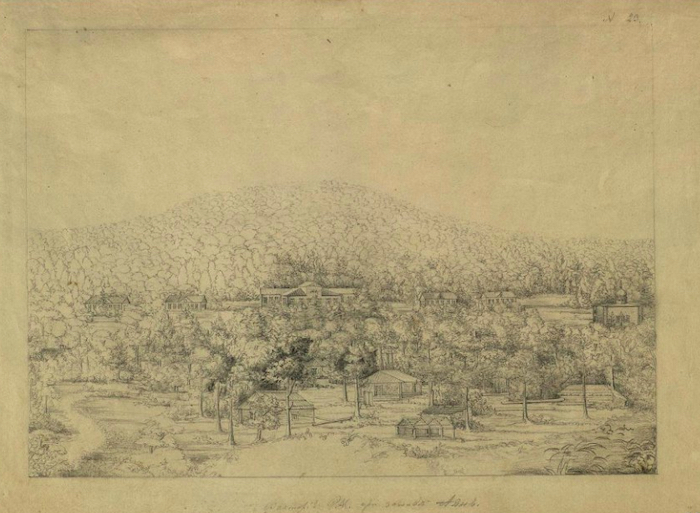

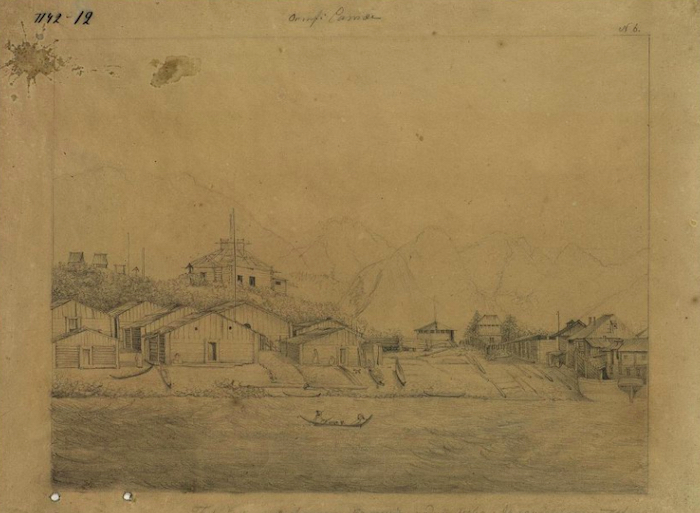

Drawing by Ilya Voznesensky. The Tlingit settlement near New Arkhangel (the City of Sitka), 1844

1142-12 / Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (Kunstkammer), Saint Petersburg