PP0076791 / Nicole Boulfroy / © Quai Branly Museum

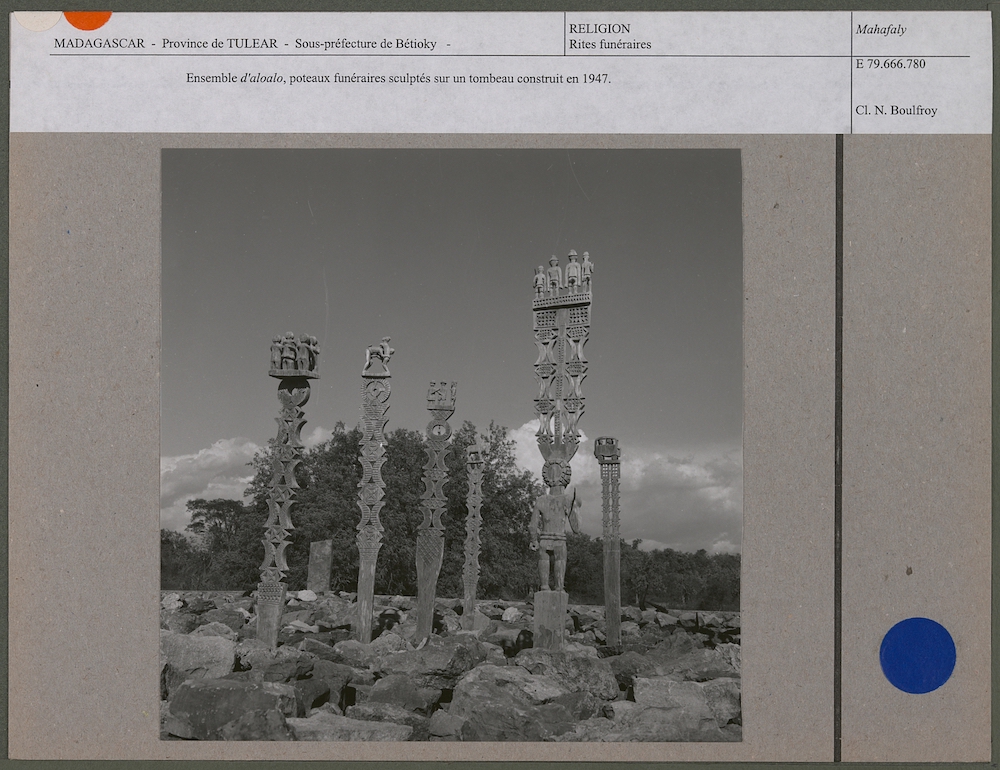

On June 12, 2020 at the Musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac in Paris, a French resident and Congolese activist Emery Mwazulu Diyabanza detached a funeral pole from Congo from its base and carried it towards the exit—with one of his four companions live streaming these actions on Facebook. On July 30, a similar episode took place at the Musée d'Arts Africains, Océaniens, Amérindiens (MAAOA) in Marseille. In September, the same group of people was seen carrying a statue out of the Afrika Museum in Berg en Dal, the Netherlands. And in October, Diyabanza reached the Louvre—already after a verdict had been passed and a court had imposed a fine for his first campaign.

Diyabanza was not actually going to steal any of those museum items—he is an activist and a member of Unité Dignité Courage group that calls for the repatriation of museum artifacts previously looted by Europeans in colonial times. Such calls are not something marginal, but in fact belong to a long-standing debate about the need to comprehend the colonial policies of the past, which also requires practical conclusions.

© Quai Branly Museum

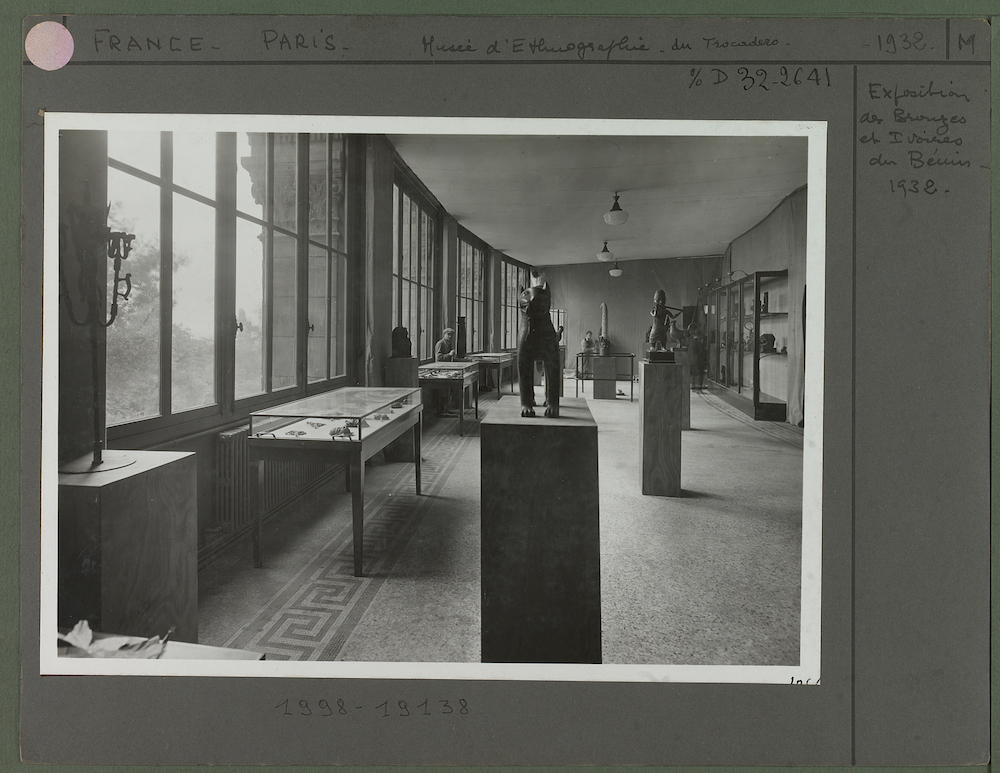

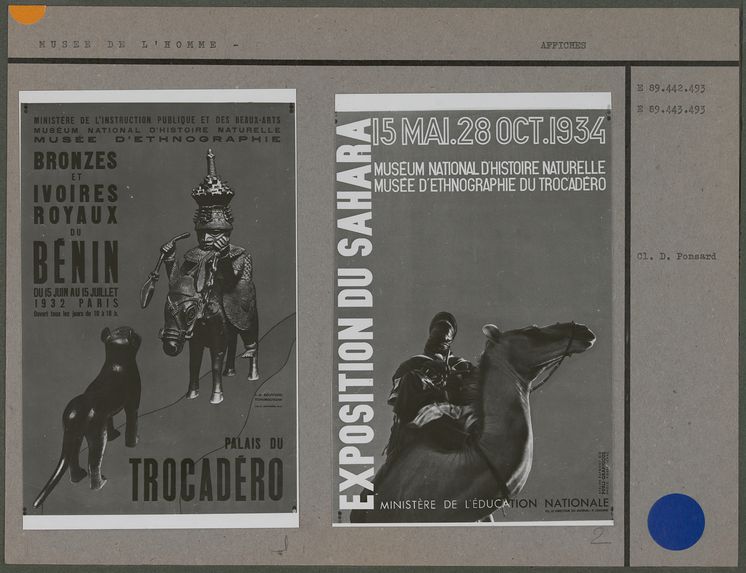

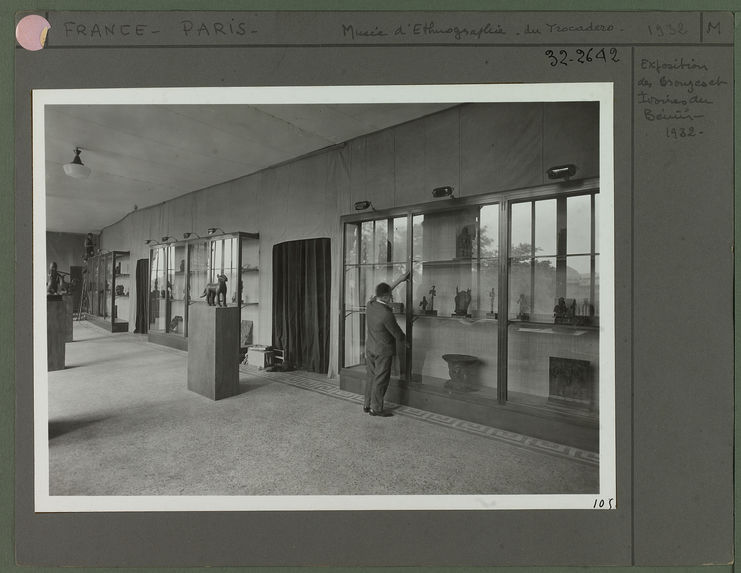

In 2020, this discussion became especially noticeable: last year the International Council of Museums published the first volume of the collection of articles Decolonizing Museology. In November, it became known that the Australian government would pledge about ten million Australian dollars towards the repatriation of Australian Aboriginal artifacts from private collections around the world. The British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum are negotiating repatriation with Nigeria and Ethiopia. But still, it is planned to be done on a long-term lease, since British law prohibits the institutions from removing objects from their collections. In October, the National Assembly of France voted to return twenty seven artifacts from museum collections to Benin and Senegal. Twenty six of them are statues and other items looted by French soldiers from the Royal Palaces of Abomey in Benin in 1892, and the last is a saber of Omar Saidou Tall, a Senegalese who fought against the colonialists. All these objects were forcibly acquired during the colonial period and they certainly make up only an insignificant part of the total number of the looted valuables.

© PF0181589 / Quai Branly Museum, 1998.2.7 / Musée d'Arts Africains, Océaniens, Amérindiens

Twenty seven objects are not 90,000—the number mentioned by the Senegalese economist Felwine Sarr and the French art historian Benedicte Savoy in a report commissioned by French President Emmanuel Macron in 2017. It is that number of objects that they consider to be unfairly confiscated and thus need to be returned to African countries if they request them. Corresponding repatriation procedures were also suggested in the report. And although Macron stated that, “African cultural heritage cannot remain a prisoner of European museums any longer,” the museums themselves are in no hurry to say goodbye to the accumulated objects.

However, neither can these museums ignore all these new voices any longer and thus they are forced to rethink their collections in the context of decolonization. For example, the British Museum offers two exposition routes dedicated to the influence of Britain’s colonial past on the collection. The route that leads visitors past fifteen artifacts (from Egyptian statues to Javanese masks) takes about an hour, and for those with limited time a shortened, thirty minute version is offered. Some museums are being completely rebuilt to reflect the new realities—for example, as a part of a $42 million renovation, a goal was set to transform the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg in Virginia from spaces that celebrate the colonial history of the region into those that would offer a decolonized rethinking. Following this transition, for example, slavery has turned from a silenced part of the region’s history into a system-forming narrative. Some museums offer artists and curators a space for projects where such rethinking becomes both a process and a result, as in Grace Ndiritu’s project Healing the Museum, which is both a performance and a workshop dedicated, among other things, to the representation of the colonial context of the museum’s collection.

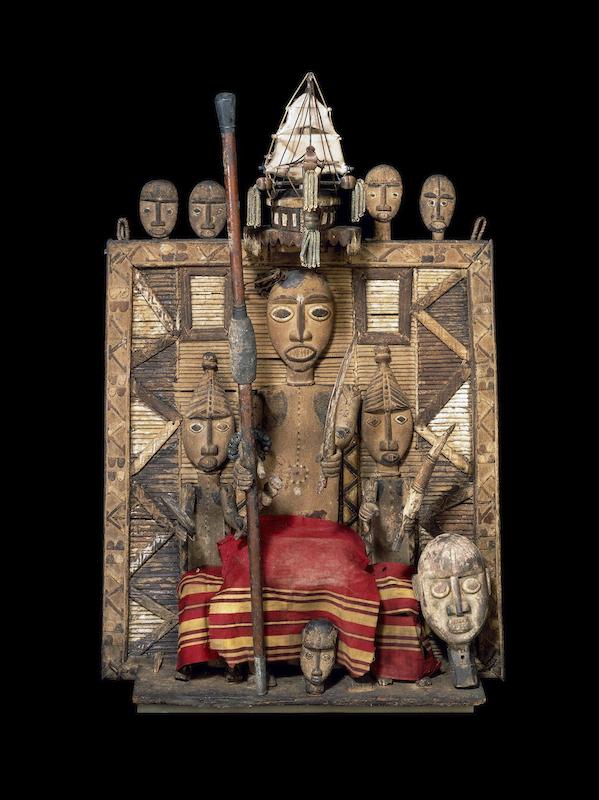

Left: A screen used in the funeral ceremony. Nigeria, 19th century

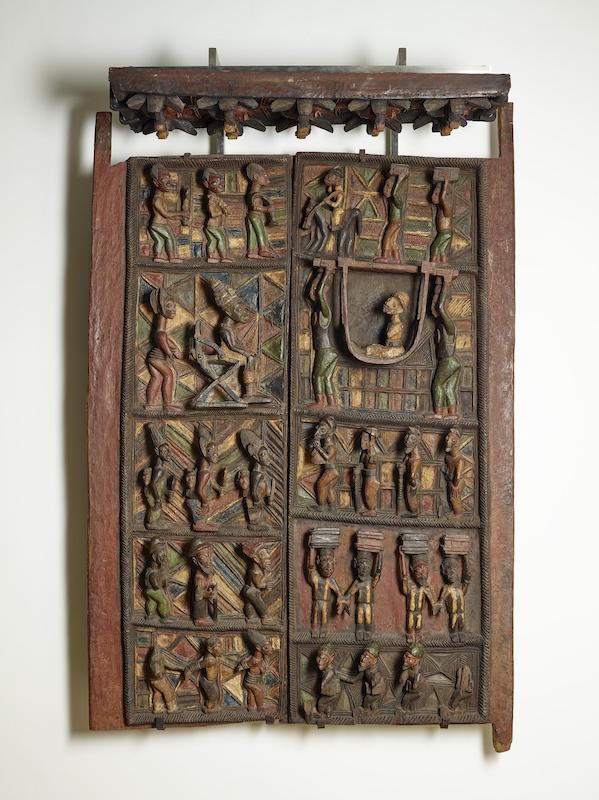

Right: A carved door leaf made for a palace in Ikera Ekiti, Nigeria (1910–1914). Shown at the British Imperial Exhibition in Wembley in 1924.

Af1950,45.334, Af1924,-.135.a-c / The Trustees of the British Museum

Staying silent is no longer possible: not long ago, on December 16th, 2020 after lengthy construction work, the Humboldt Forum—an expensive large-scale museum project—opened in the Berlin Palace. What do people say about it? Almost all that one can hear about the Forum is rumors about the Benin Bronzes from the collection of the Ethnological Museum. Nigeria, on which the territory the palace of the Kingdom of Benin’s ruler used to be located, has long been insisting on the return of the plaques. The same Ethnological Museum returned two mummified Maori heads to New Zealand , and to Australia—the mummified bodies of two children and bones in a wooden coffin that had belonged to Australian aborigines. Maybe it was the fact that these museum items were actually not just material objects, but human remains that played a role.

In June 2020, Christie’s auction house sold two wooden sculptures that were once located in sanctuaries on the territory of Nigeria. The auction took place amid protests: Princeton University professor Chika Okeke-Agulu, who came from the same region where the sculptures were made, wrote that they were taken as a result of looting during the civil war in 1967–1968. The auction house replied that the papers were in order and the last owner had acquired the items legally, so formally everything was fine.

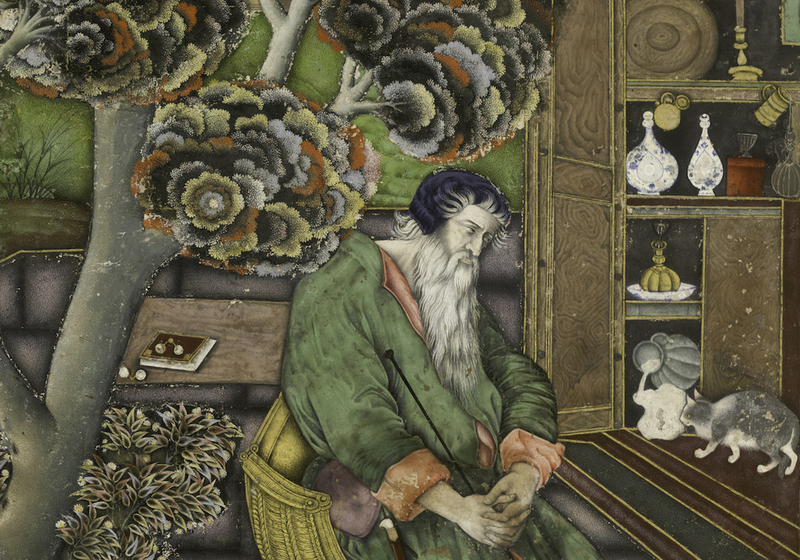

© Christie’s

In this case, the point is not only about the circulation of artifacts across countries, but also about public and private institutions returning the items to the communities that had previously possessed them. As is the case in Canada, where for decades museums have been handing over items to descendants of indigenous people that were unlawfully seized from their predecessors. At the same time, new cultural centers are being created that belong to these communities and in which the museum component is combined with the returning traditional practices to life.

Thus, the process is unfolding, although slowly. What is returned is measured in units, and what is still left in museums—in the tens of thousands. Justice-related issues clash with those of legal law; the interests of communities—with the interests of owners and sometimes paternalistic attitudes on the part of yesterday's colonialists. For example, doubts are often expressed concerning the inability of African countries to take care of the returned objects’ safety. But while the year 2020 did not become a turning point, the pressure on Europe will keep growing (as will the pressure from inside), and questions about the ethics of museum collections will not disappear automatically.

Translated from Russian by Olga Bubich