The Portland Art Museum

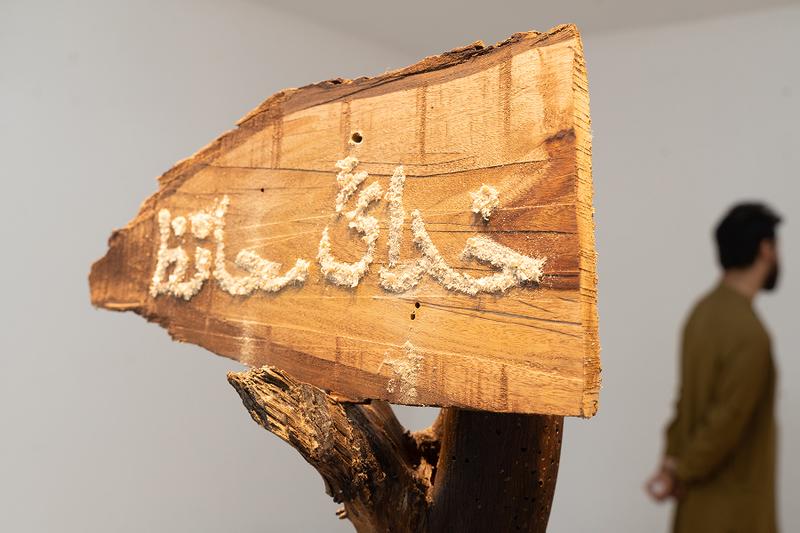

On Sunday, February 10, 2013, more than one hundred people, most of them representatives of Canada’s indigenous peoples, gathered on the steps of the Legislative Assembly of the province of British Columbia to participate in a ceremony that had not been performed since the 1950s. It culminated with Hereditary Chief and artist Beau Dick, together with his cohorts, breaking a copper, thus shaming the federal government for its environmentally destructive actions and infringement upon the interests of the First Nations.

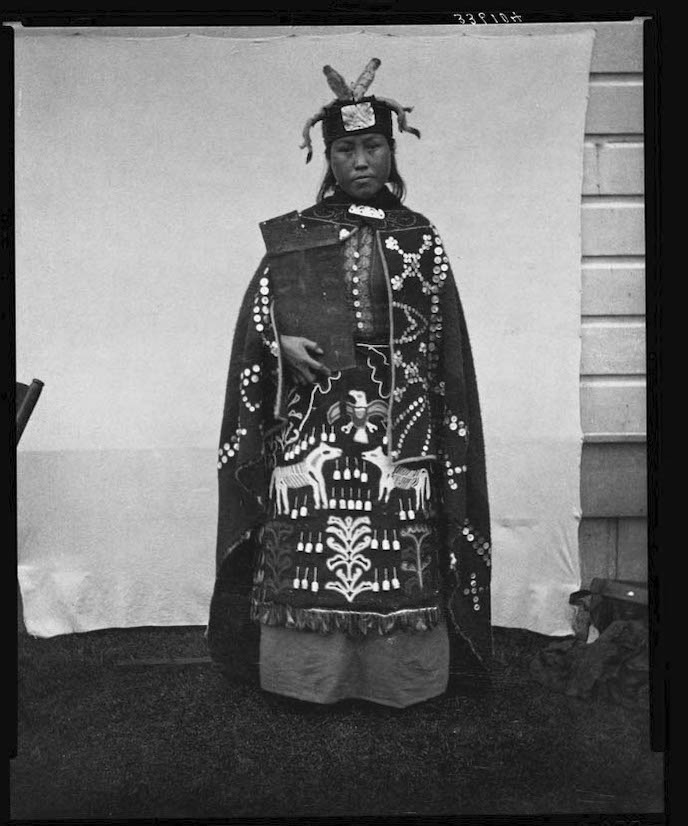

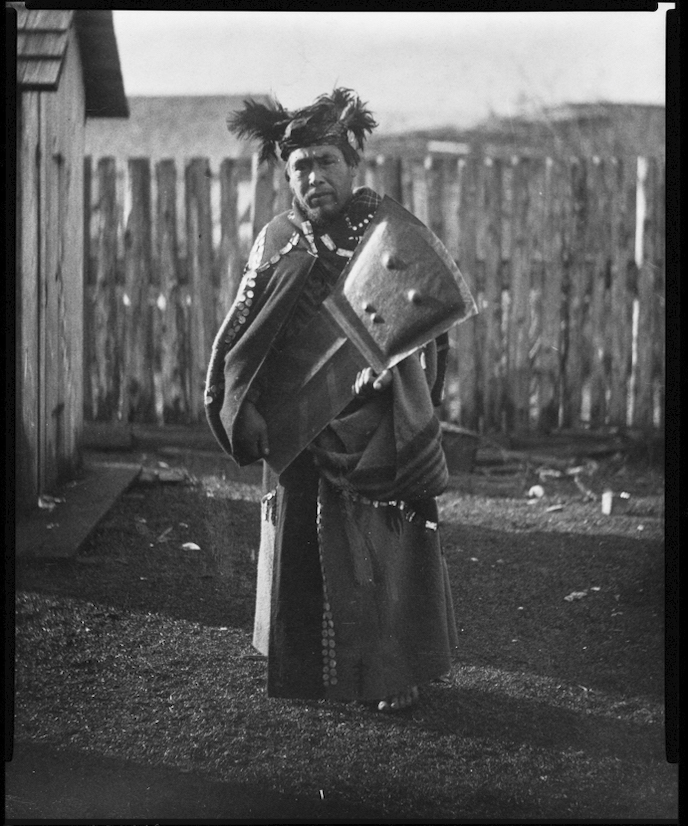

The copper, or tlakwa as it is called in the language of the Kwakwaka’wakwKwakwaka’wakwThe name Kwakiutl is no longer used, as it is considered imprecise. Instead the name “Kwakwaka’wakw” (literally, “those who speak Kwakw’ala”), which the people call themselves, is accepted. people, resembles a shield with a T-shaped ridge and symbolizes its owner’s wealth and high rank. Passing from owner to owner, the copper grows in value: if it was purchased last time for a 1,000 blankets, then the next purchaser must offer at least 1,001, but more likely 1,100. If one chief wants to humiliate another, he can cut off a piece of his copper. To avoid shame, the other chief must respond by breaking a copper of equal or greater value. Each copper is unique and has its own name: sometimes referring to an animal, like “Sea Lion” or “Great Killer Whale,” and sometimes emphasizing the copper’s worth, like “Other Coppers Are Ashamed To Look at It” or “Making the House Empty of Blankets.”

The American Museum of Natural History

“The copper is a symbol of justice, truth and balance, and to break one is a threat, a challenge and can be an insult . . . there should be an apology,” said Beau Dick, commenting on the ceremony at the Legislature. The ritual of breaking copper became part of the Idle No More movement, led by indigenous peoples protesting legislation that threatens so-called guaranteed rights, which the native populations of the US and Canada enjoy according to treaties between tribes and the governments of those countries. Over time the movement broadened its agenda to include many social and ecological problems and in 2014, Beau Dick repeated the ritual with an even greater crowd of supporters, now on Parliament Hill in Canada’s capital Ottawa. He declared, “In breaking this copper we confront the tyranny and oppression of a government who has forsaken human rights and turned its back on nature in the interests of the almighty dollar, and we act in accordance with our laws.”

Before becoming a leader of political actions, Beau Dick was known as an artist who made traditional masks and organized potlatches—ceremonies for the exchange of gifts, which involve the performance of ritual dances. However, it would not be right to separate his artistic and social-political activities, for the exchange of gifts is not just a symbolic gesture but the foundation of the social-economic organization of the communities that practiced potlatch in the not-so-distant past and are now trying to revive this tradition. Anthropologists, sociologists, and economists like Marcel Mauss, Georges Bataille, Lewis Hyde, Marshall Sahlins, and David Graeber analyzed this practice of the indigenous peoples of the Pacific coast of North America in their writings on the special economy of the gift.

Royal British Columbia Museum

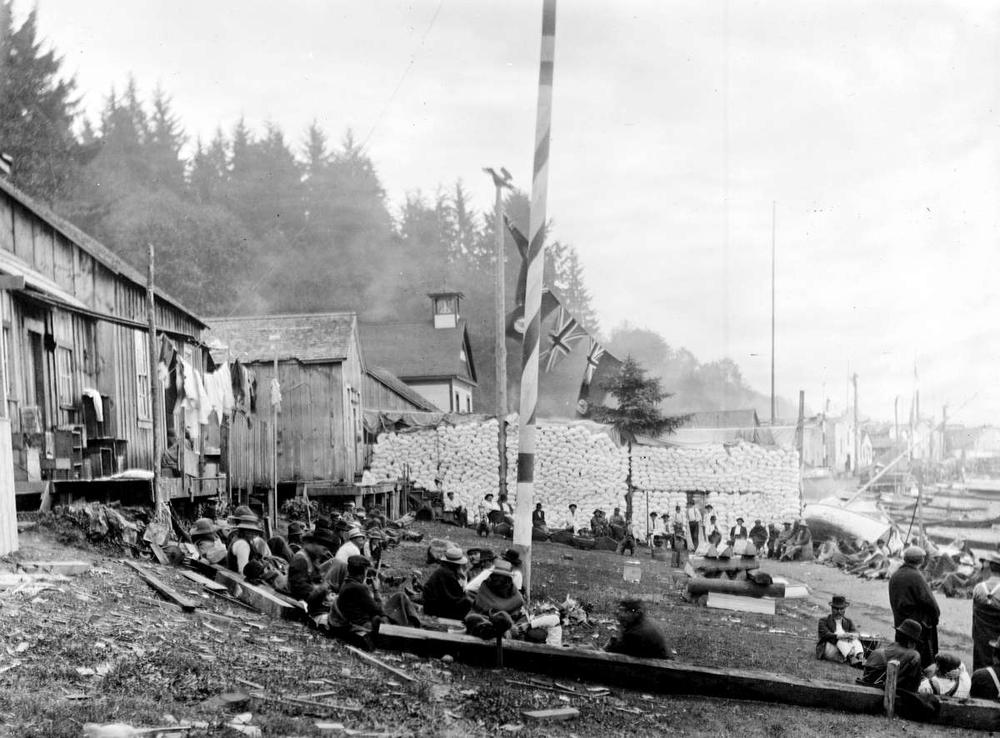

During the potlatch, its hosts traditionally gave away—and later began destroying—personal property, thus demonstrating their social status, investing in the future, and proving that the spirits favor their family. During a great potlatch in 1923 a billiard table was among the things destroyed. In The Gift, French anthropologist Marcel Mauss wrotewroteMauss, Marcel. The Gift: Forms and Functions of Exchange in Archaic Societies. Trans. Ian Gunnison. New York: W.W.Norton & Company, 1967 (1923), p. 36. that the potlatch ceremony played an important role in Kwakiutl culture through the idea that each thing that was destroyed or given away would inevitably return to its owner or his descendants. “For the potlatch is more than a legal phenomenon; it is one of those phenomena we propose to call 'total.' It is religious,mythological and shamanistic because the chiefs taking part are incarnations of gods and ancestors, whose names they bear, whose dances they dance and whose spirits, possess them.”

The essence of the potlatch, the attitude of colonizing settlers toward it, Beau Dick’s traditional masks, and museum collections are bizarrely connected. In 1884 the Canadian government banned potlatches as senselessly extravagant, i.e., essentially anti-capitalist activity. The ban lasted until 1951 and it was even enforced through raids. For example, in 1921 during Christmas week there was a huge five-day potlatch in ‘Mimkwamlis on Village Island. Forty-five people were arrested; twenty-two were sent to jail. Later, their time was reduced on the condition that the masks, coppers, headdresses, and other items used in the potlatch be handed over to the government, along with an official promise that the accused would refrain from participation in such events in the future.

Johnny Drubble's coppers, confiscated in 1925 and donated to Edward Sapir at the Canadian Museum of History. Returned in 1979

U'mista Cultural Centre

The objects confiscated in this way were sold to individuals, such as George Gustav Heye, whose collection later became the basis for the National Museum of the American Indian, which New York branch now bears his name. Many other museums and private collections have grown in a similar way. The process of repatriating valuables, now a hot topic of discussion in the artistic community, was set in motion back in the late 1960s. In the late 1970s–early 1980s, the U’Mista Cultural Center in Alert Bay and Nuyumbalees Museum in Cape Mudge were opened upon the repatriation of several objects; today they both serve as museums and public spaces for the revival of practices from the past.

So how did the Canadian government react to being shamed by the ceremony of cutting copper, led by Beau Dick? They sent the copper fragments to a museum.

Translated from Russian by Larissa Babij