FBQ. 8163., FBQ. 8478., FBQ. 7732 / Sheikh Faisal Bin Qassim Al Thani Museum

Objects presented within the exhibition Qatar between the Sea and the Desert. Art and Heritage at the Russian Museum of Ethnography, can reveal various narratives. Looking at selected artifacts, Olga Slepukhina discusses the pearl industry of the Persian Gulf.

Pearls are mentioned in the Quran six times and all the references have to do with the description of the Garden of Eden and the blessings that await believers there—pearls are a metaphor used to emphasize the beauty and splendor of paradisesplendor of paradise“But Allah will surely admit those who believe and do good into Gardens, under which rivers flow, where they will be adorned with bracelets of gold and pearls, and their clothing will be silk.” (22:23; tr. Dr. Mustafa Khattab, the Clear Quran); "And they will be waited on by their youthful servants like spotless pearls." (52:24, Dr. Mustafa Khattab, the Clear Quran). For the inhabitants of present-day Qatar and other countries of the Persian Gulf, it has never been just a beautiful object, it was its high cost that mattered more.

For a long time, the region’s economy was based on the pearl trade, which went into decline only in the 1900s-1930s due to the spread of cheaper cultured pearls from Japan, the world wars, and the Great Depression. Prior to this, “Victorian Britain and the rest of Europe saw in a pearl a tangible symbol of the romantic OrientOrient Carter R. The History and Prehistory of Pearling in the Persian Gulf. Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, 2005, № 2, P. 189.,” and a strong demand from Europe, India, and later the United States kept prices for pearls rather high and “any economic recovery in Europe and America was immediately followed by an increase in the value of pearlspearls Carter R. The History and Prehistory of Pearling in the Persian Gulf. Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, 2005, № 2, P. 189.

..Ibid.

”

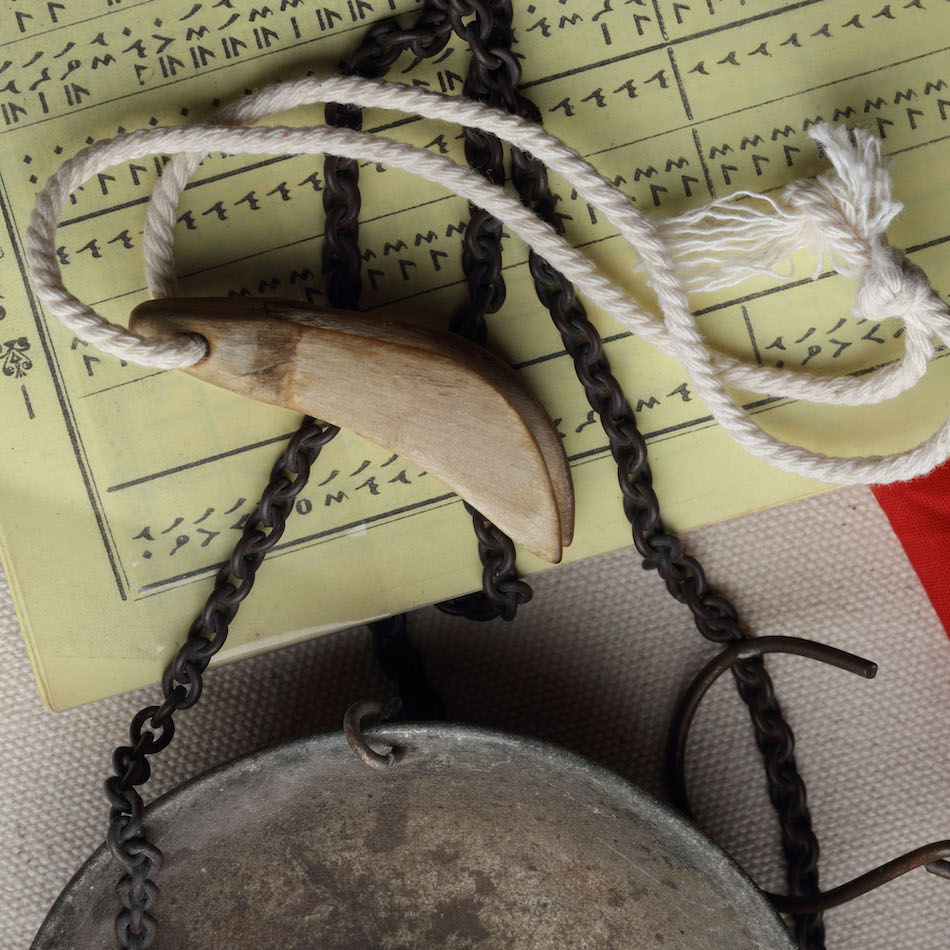

Ships of pearl divers were sometimes compared to a traveling market, and buyers always showed up there with their own “cash desk”—a special casket that served any pearl merchant as a permanent companion. Such caskets were often made of rosewood or other durable timber and differed a lot in design: they could be modestly decorated or ornamented with rich carvings and look like either a large chest or a medium-sized box. However, caskets always contained everything the merchant needed—scales, strainers, weights, and notebooks. Using these instruments, the trader assessed pearls based on their quality, weight, color, shape, and luster. If the decision to purchase a pearl was taken and the price was good, the gemstone ended up in the same casket.

FBQ. 208. / Sheikh Faisal Bin Qassim Al Thani Museum

After the Gulf countries were allowed to become part of the global market, pearls became a symbol of poverty and deprivation. Despite the high costs, the wages of those involved in their extraction remained low and the working conditions harsh, since Britain and the local ruling families opposed modernization. In 1930, the diplomat Sir Hugh Biscoe wrote that the British were spreading rumors about the dangers and risks of modern diving equipment. As a result, in the 20th century divers rarely used modern diving suits and went on with the simplest equipment and tools, the same as those mentioned by Al-Masudi back in the 10th century. Thus, on the one hand, Britain provided demand and promoted the development of local pearl hunting, and on the other, reduced its competitiveness by prohibiting modernization.

Clothespin-shaped nose clips were made of tortoise or lamb bones, as well as other animal bones. The diver used such a clip to close the nostrils to prevent water from entering, whereas the stone helped to reach the bottom faster and thus saved time—something particularly valuable underwater. Such stones were mentioned in “The Epic of Gilgamesh,” and although Gilgamesh did not hunt for pearls, but was searching for the flower of eternal youth, the description of his immersion in the ocean is considered one of the earliest mentions of the diving profession.

FBQ. 2055., FBQ. 2056 / Sheikh Faisal Bin Qassim Al Thani Museum

Oil production began in the 1950s and the local society underwent rapid and significant changes in all spheres of life. Pearl hunting, until recently perceived as a part of everyday life, is now seen more as historical heritage, a craft of ancestors that brings together the present and the past.

Literature, festivals of traditional culture, museum exhibitions, and projects aimed at the development of tourism romanticize the memory of pearl hunting. The dangers and all of the hardships sailors faced while hunting for pearls are often described only to emphasize the heroic nature of the profession, and the strength and courage of ancestors.

Another simple tool is a short knife with a slightly curved metal blade and a wooden handle. The knife served a purpose at a very important stage—it was used to open the shell and extract the pearl, should one be lucky to find it. In the case of a successful deal, the diver who found the pearl in the shell would receive a reward—money, a ram, or something else. The process of shell-opening was closely monitored—thefts were relatively rare but sometimes they did happen. The thief was punished by a beating in front of the other co-workers. Also, he lost his share of the pearl’s sale, was banned to further participate in shell-opening, and, if he had managed to swallow the pearl, got his stomach pumped.

FBQ. 2057. / Sheikh Faisal Bin Qassim Al Thani Museum

On the one hand, this past is presented as a time when society lived a modest and honest life, in harmony with nature. On the other—an emphasis is put on the hardships sailors experienced, and the conclusion is made that such trials should not be repeated in future. Such a combination of contradictory narratives is, to one degree or another, characteristic of all the countries that use the memory of pearl hunting in the construction of their ethnocultural identity. At the same time, some aspects often remain in the shadows—for example, the above-mentioned dependence on the world market or the fact that the difficulties pearl divers faced were not only physical.

Young people involved in fishing expeditions re-enactments confirm that this experience helped them to feel a connection with the past and become more aware of the hardships their ancestors experienced at sea. Nevertheless, the past is unlikely to be recreated fully, and all the participants of such reenactments know that at the end of the journey they will return to their comfortable homes and usual food. In addition, the participants of these festivals immediately become, for example, divers, and do not have to follow a long career path, starting work at the age of ten. For them, their whole next year would never depend on whether the ship’s crew would be able to find and profitably sell enough pearls, and, if unlucky with the weather, they would never have to figure out how to pay off their past debts. Divers borrowed money from captains, captains—from pearl traders, who in turn often owed money to larger traders. If the season was not good and paying off the debt was not possible, the payment was postponed to the following year with the sum consequently growing bigger and bigger.

Perhaps that is why in the modern memory of Qataris there is no emphasis on the economic and social standing of people who performed various roles in the chain of pearl hunting and trade and the tools that were once used by both sailors and merchants end up in the same display.

Translated from Russian by Olga Bubich