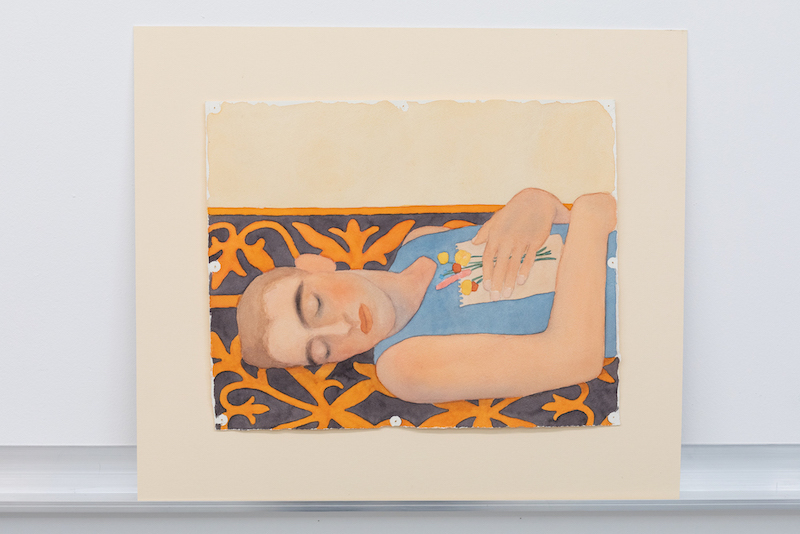

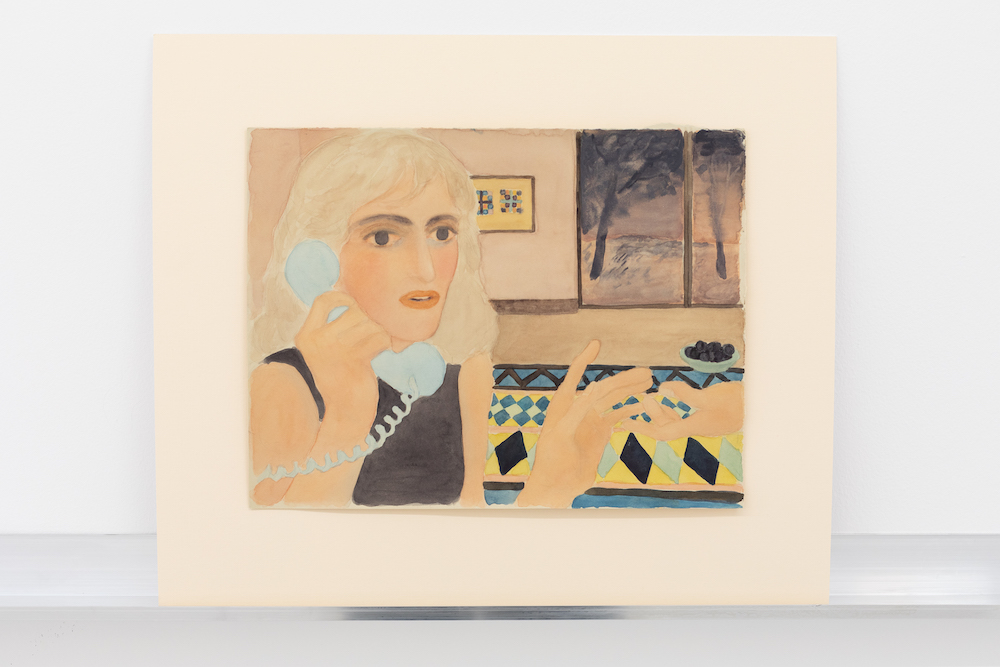

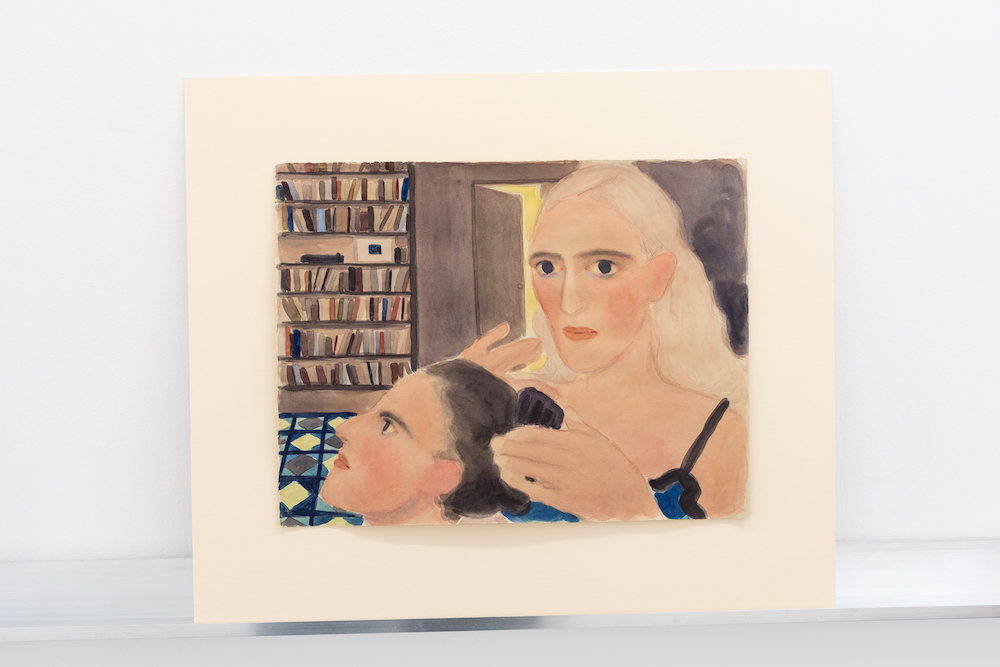

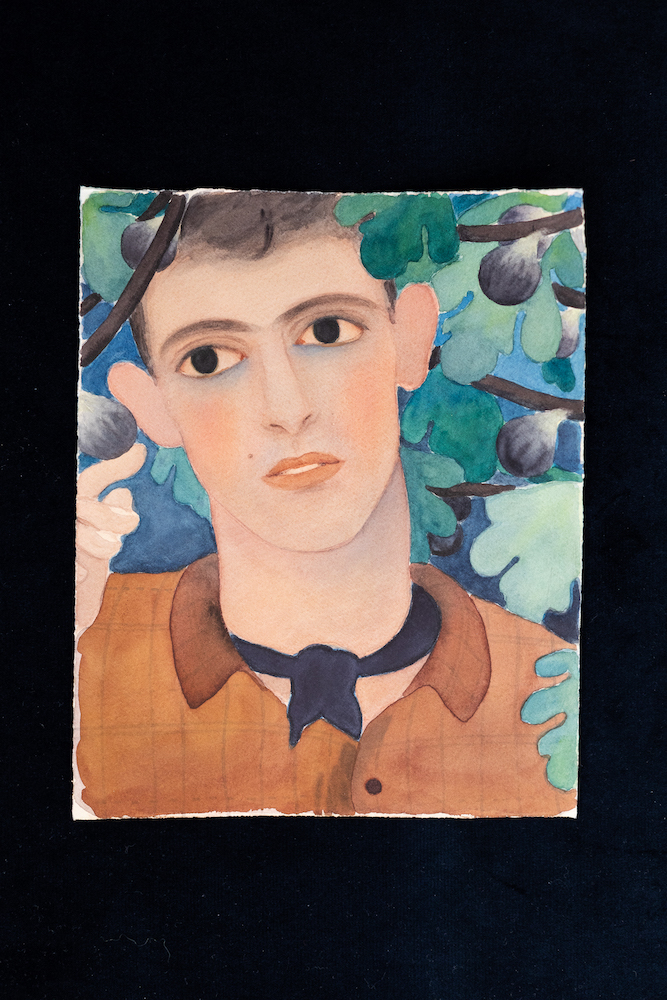

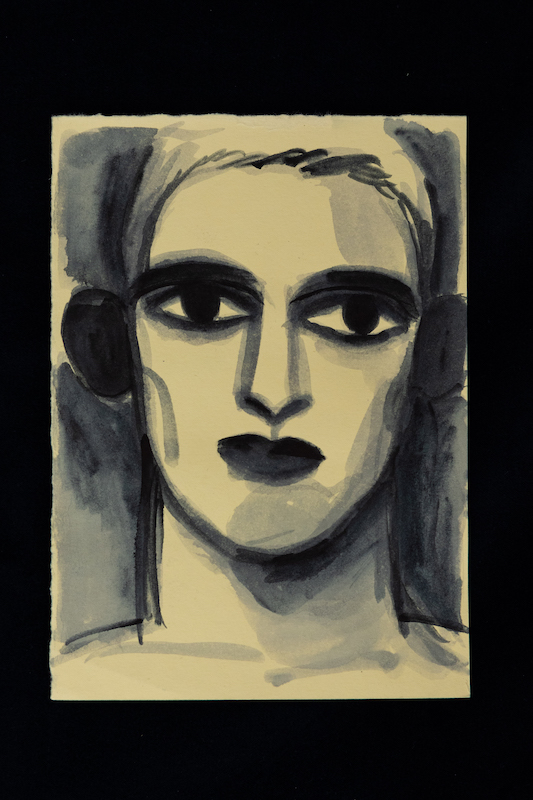

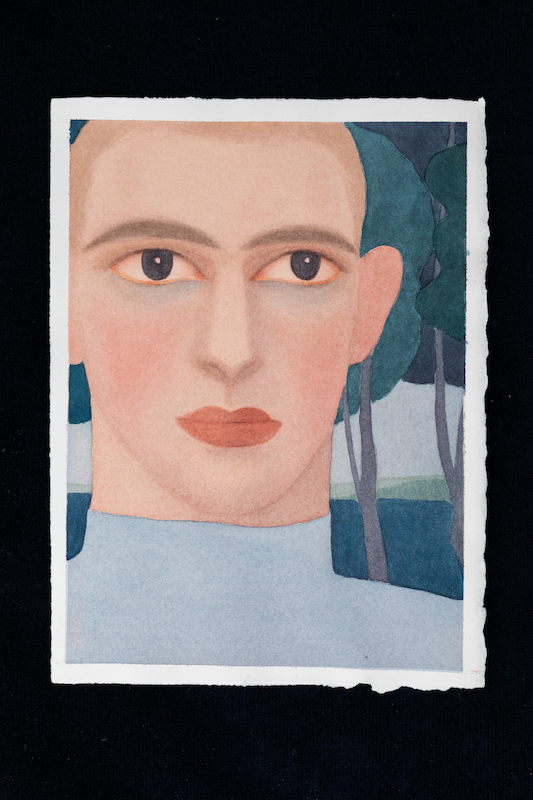

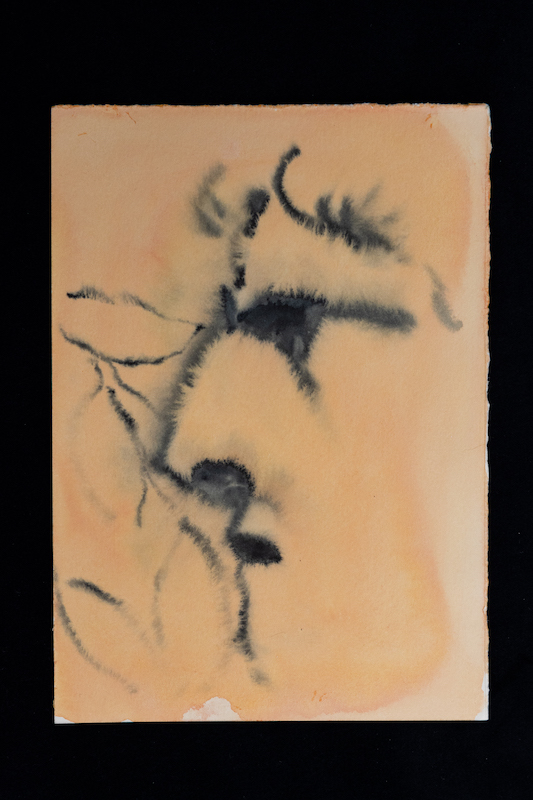

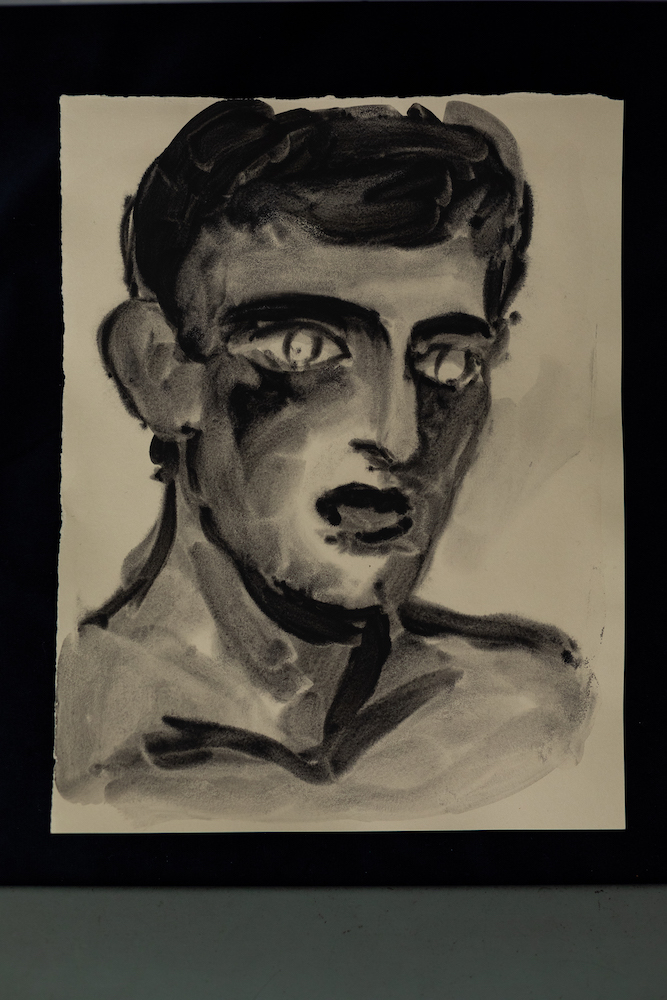

Till April 30, сцена/szena gallery is hosting the first solo exhibition of Akhmat Bikanov, an artist and architect from Kabardino-Balkaria. Akhmat shared with us his memories of childhood in Nalchik, reflections on the therapeutic power of nature and emotional attachment to particular objects.

Nalchik and Kabardino-Balkaria occupy an important place in my heart and are primarily associated with family and nature. Nature is a part of me and, in general, of every one of us. It is good to find yourself somewhere in a gorge, in the mountains, by a mountain river, watching the hidden life a step away from you. I perceive this experience as therapy, as a kind of purging, or as an internal transformation, because after such observations you develop a clearer perspective on many things. Difficulties do not disappear, but you start perceiving them in a different way. However, this effect has a limit: when you get back to a big city, after a while everything is again covered with a veil—due to misunderstandings with people and yourself or some other contradictions. All these keep building up in me until I feel the need to return, to take a walk along the river, to look around and answer honestly to myself what I really need and what it would be better to let go.

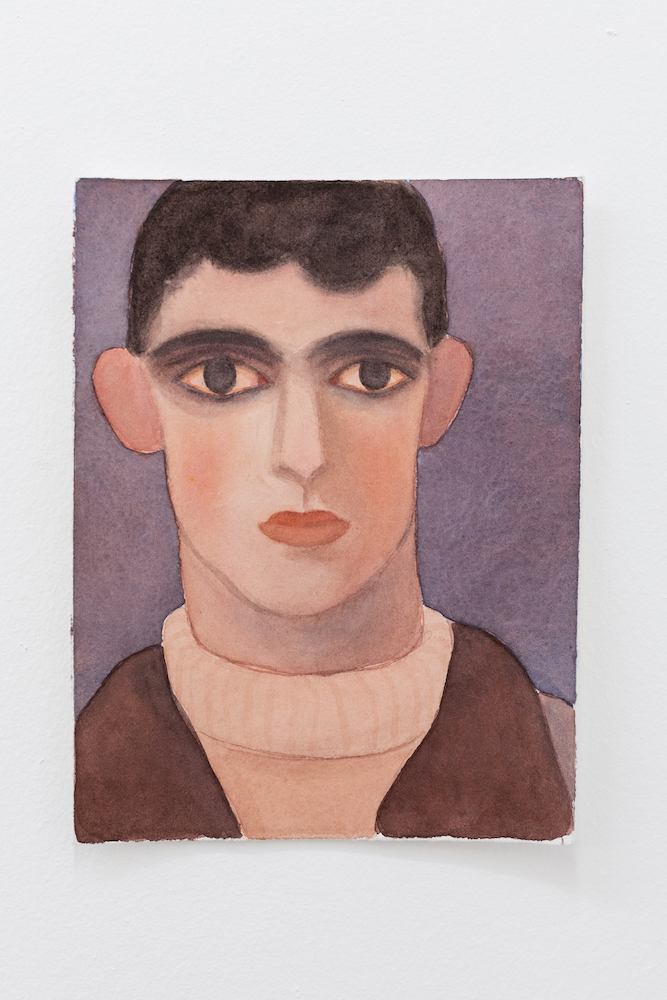

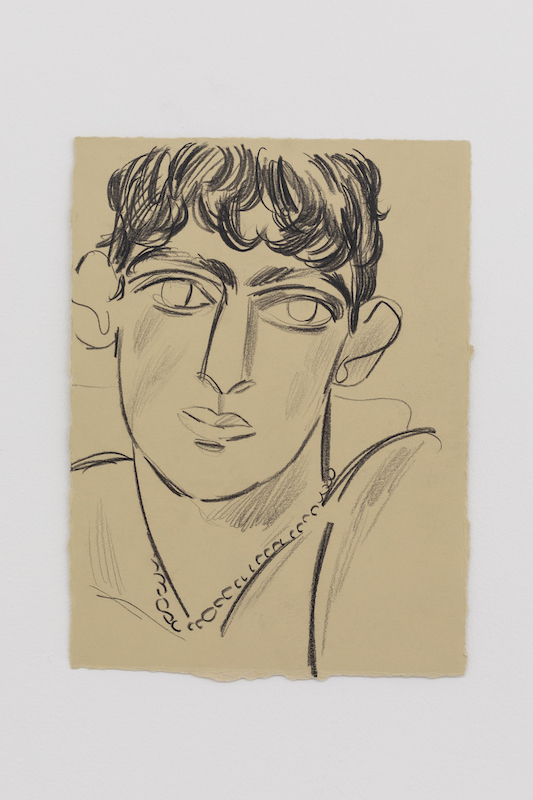

In the 8th or 9th grade, I came across some information on the Moscow College of Architecture and Construction No. 7 on the net, and it was then that I saw a clear picture of my future. I wanted to enter that specific educational institution and my mother immediately supported me, but it took a while to persuade my father to allow me to travel to Moscow. Back then, the fact that my mother quit her favorite job, left home, and moved with me seemed something natural, but now I approach her decision in a completely different way. It was a sacrifice and I just want her to never regret it. Mom is a musician and honored artist of our republic—she plays the accordion. She worked for twenty six years in the folklore ethnographic dance group Balkaria and as a child, before and after school, I often visited her at work and watched the rehearsals. I liked the theater because everything there was somehow fabulous and unlike the outside world: I touched the fabrics of costumes embroidered with beads and colorful gemstones, walked around the large concert hall that looked a bit gloomy and mystical with no lights on, often imagining myself an artist on stage . . . It appeared to be completely unlike what I experienced in my everyday life. I really miss that time and cherish a little dream—to watch the performers when they get ready for the show with young women and men dressing up and putting on makeup. At this particular moment, some kind of metamorphosis occurs, and the people you personally know, right in front of your eyes, transform into someone who looks and feels totally different.

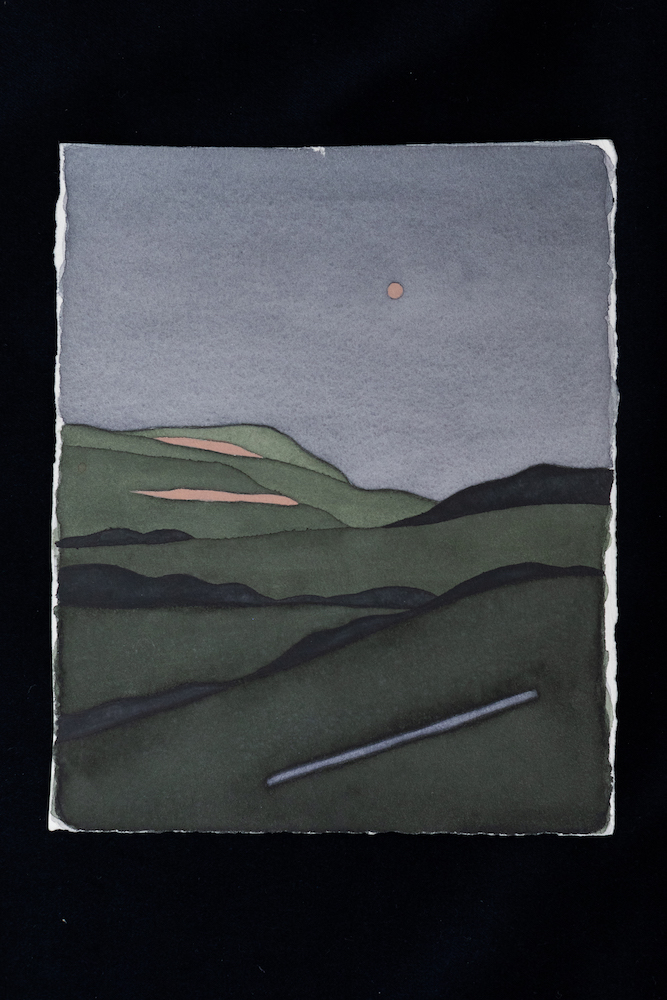

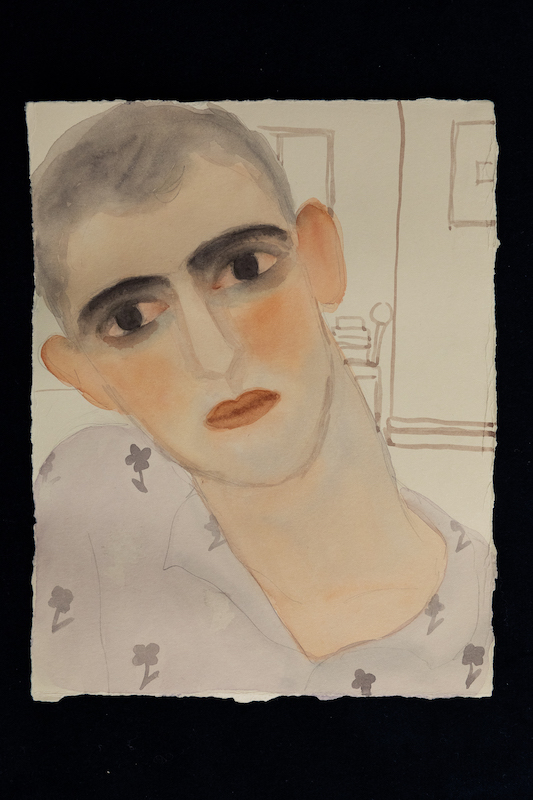

I don't know what could be called the beginning of my career. I was described as someone who always painted a lot. As a child, I got acquainted with art through books, while looking at illustrations and redrawing my favorite images through carbon paper. I liked Ancient Egypt, Ancient Greece, and a little later—the Renaissance most of all. I always enjoyed the smell of pencils, especially the smell of shavings you get after sharpening. Now I adore the smell of honey watercolors or wet paper: when preparing them, I tint some works with a saffron solution and for a while they emit amazing smells. In general, I do it to get rid of the white color in the background. I endlessly love blue—it seems the richest and most noble colour. Moreover, it is my mom's favorite one. The songs I love also contain the word “blue,” which in English also refers to a person’s inner state. When I miss home, I draw sketches with mountains and a dancing man and right in front of me I see the evening sky in late summer—dark blue and liberating. To me, dancing with nature somewhere up in the mountains with nobody around feels like absolute happiness.

When I used to come to Nalchik during my studies, I spent no more than a month there and already a week after I missed certain places in Moscow: Fayum portraits in the Pushkin Museum, my friends, and the feeling of constant motion. In the same period, I was working in an architectural bureau. During those times I wanted to return to Moscow because in Nalchik I felt like I was starting to dissolve, I was worried that I would not be able to reach absolute tranquility after such troubled states of mind. It really bothered me. But during the quarantine, everything changed: I talked with my friends and all together we remotely graduated from Moscow Architectural Institute. I realized that returning to Moscow made no sense. At that time we were defending our diplomas and it was very embarrassing for me to tell my friends who were then all staying locked up in their apartments that I was home, where everything was calm and I was enjoying the view of the garden outside and listening to the endless singing of birds. Then summer began and I started travelling to the mountains and this time it was Moscow that was dissolving in me and I did not want to return there at all. Days and nights were merging. Everything was somehow timeless. I did feel lonely, but I experienced this loneliness as a sweet pain in my chest.

One episode happened in the summer. During some cleaning, a beautiful handmade cradle was found—later I learned that this was where I had spent the first months of my life. Initially, it was going to be burned, but fortunately I found out about it in time and managed to bring it to my room. Now I use the cradle to store paints, small canvases, and books—somethings that are meaningful to me. I also keep my stones there—I try not to forget where I found each of them and when I’m holding them I feel like I am touching my home’s soul. I experience my home as something supreme. I am pleased to touch my stones, the very process calms me down and brings me closer to the roots: if I feel tension, I touch the objects and explain to myself what they are—prickly, rough, or smooth. Sometimes I give these special stones to my close friends.

I would also like to tell you about the Karachay-Balkar felt carpets—kiyiz. Such carpets were made mostly by women. Working with felt was not easy: once it was rolled up, women were to felt them while at the same time pouring hot water on the material. The process could take up to several hours and it was both about communication and creativity—with ritual songs, feast, and games involved. I do not know if anyone owns this craft at such a high level now. I love the fact that these items are so difficult to make and that the process of their creation is closely connected with communication. Such carpets need to be stored in safe places and we should be proud of them. Moreover, the older the carpet or any other handmade item is, the more valuable they are. And I feel sorry that many do not understand it—I mean these craftswomen’s grandchildren or children, for example. Still, the greatest distance is something that separates one person from another. It is sad when carpets and other valuable items are thrown away or burned. Maybe it happens because of the desire to get closer to the ideal of cleanliness: why do we need a shabby handmade carpet when we can buy a new manufactured piece without the risk of blushing when receiving guests?

Another fabulous item that I have is my grandmother's dowry chest. I use it to keep sketches or works that have not yet taken their final form. In future I would like to use this chest as a part of my exhibitions. Such objects are like threads that connect us to some places or people and I find them to be really important. Moreover, all of us, with all our disturbances, doubts, and confusion, actually need them—as something that could structure this inner chaos. So, both the chest, or, for example, a box my grandfather bought at an auction when he was young, play these roles. I am very much attached to these objects and feel that they reflect our lives and are able to speak for us. There are things we collect and cannot throw away because to some extent we tend to animate them.

By the way, one friend of mine has a carpet made by one craftswoman whose grandchildren were going to throw it away at first, but in the end they offered it to her. It is strange to think that someone could come up with the idea of getting rid of such a thing. But now, when I visit my friend in her Moscow apartment, I lie on the carpet and feel like I’m floating back home. It has a few flaws that somehow only complete it aesthetically, making it even more beautiful. The carpet is imperfectly perfect. You see a hole or notice that the color of the ornament takes a different shade in some part, but you still love it—and this is what I enjoy most. The same can happen to people. We are living in a dangerous time, everyone wants to be neat, is afraid of mistakes and hardly forgives those who make them. Watercolor remembers everything, and, while working with it, one can hardly fix anything. But it is exactly this thing that also attracts. So, I am learning from it—I allow mistakes to happen and I see in them a certain meaning.

All pictures courtesy сцена/szena gallery and Akhmat Bikanov

Translated from Russian by Olga Bubich