Artist Faina Yunusova uses examples from photography in Central Asia to consider critical questions related to agency, control, and colonization. How does portrait photography construct identities and to what extent are they malleable? How does an external gaze give birth to the image of the Other? Yunusova reveals new truths through a combination of personal reflections, historical contexts, and comparisons between the treatment of photographic subjects.

This text draws upon images from my family archive and other representative photographs from Central Asian countries. I wrote my thesis on the construction of identity in Central Asian photographs, and in this essay, I aim to use the collected material to convey the pain and torment of the lifelong search for one's own identity.

I was growing up in Uzbekistan in a multi-ethnic family. We spoke Russian and though I didn’t immediately realize it, the language served as a tool of oppression and power. When I came to study in Moscow, I encountered another aspect of coloniality—everyday racism. At that time, I had no access to post- and decolonial theories, and it seemed normal to me that if I was called "black" (or "churka") in the supermarket, it was acceptable because I was just a guest in a country that was foreign to me.

Moving to Germany provided me with the opportunity to examine these relationships from a third perspective, prompting me to ask myself questions. New acquaintances fueled my reflections. Upon hearing my accent, they would invariably ask, “Where are you from? Who lives in Uzbekistan? Why is your mother tongue Russian?” This curiosity compelled me to trace the origins: how did it happen that I turned out to be who I am, and what influenced it? This essay represents a rough, yet I hope, accessible attempt to comprehend the process of identity formation, both in my case and generally.

In my family archive, there is a photograph of me and my family posing against a special background in a Tashkent amusement park. When I carefully examined this picture a few years ago, I was struck by a rather strange set of objects. How can an umbrella with a Coca-Cola inscription, a Nivea ball, and soft toys be considered desirable attributes for a background? I remember that my little sister and I had to wear our best dresses because we were taking a “keepsake” photo. In other words, the photo was not taken as a joke but as a worthy addition to the family album.

I decided to inquire with my relatives about the meaning and purpose of such photographs, which were a common practice at that time. I learned that the attributes in the background were not merely objects but symbols of wealth and status. One could say they were symbols of the Western “progressive” civilization to which people aspired to belong. I recall that many Uzbeks specifically traveled to the capital to take such a photograph, preserving it as a memory of their connection to an alternative life.

Can one break free from such imposed constructs? Or, perhaps, creating a myth about oneself based on these constructs—is that also a form of freedom, an assertion of a malleable identity? A curious paradox: the desire to capture one's best version, to create an image in a photograph that has nothing to do with reality, has motivated me to delve into the colonial past.

***

Photography appeared on the territory of Central Asia in the second half of the 19th century. The Russian Empire was seizing new territories, resulting in the formation of the Turkestan General-Governorate, with Tashkent as one of its two regional centers. The state paid military photographers and also commissioned ethnographic albums that could create a picture of Turkestan society and its social groups. Western traveling photographers also visited Turkestan during this time.

By the end of the 19th century, much like in various Russian and European cities, an increasing number of photo studios started to appear in Tashkent, where everyone could be photographed for a fee. By 1910, the number of photo studios had surpassed two dozen, and they also emerged in other cities in Turkestan. These studios were mainly opened by non-locals and Turkestanis who learnt from them, adopting the style and photographic practices (for example, Khudaibergen Devanov, who is now considered the first Turkestan photographer, took his first lessons from amateur photographer Wilhelm Penner near Khiva and later studied photography in St. Petersburg).

My attention was particularly drawn to studio photographs, where images were crafted using attributes and special backdrops. The result was an aestheticized reality, shaped at every stage by the creative will of an individual or a group. Studio clients could create the best image of themselves to which they aspired, while photographers brought that vision to life.

***

The style and trends in Central Asian photography mirrored Western ones but took on entirely different meanings.

At the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, staged photography became an accessible means of self-expression for Europeans, offering a way to capture their most dignified persona. In other words, photography for the white man became a democratic tool for transformation, portraying individuals in various social roles and contexts. It served as both entertainment and a social elevator, particularly for less affluent groups in society.

But compare this with the memoirs of one of the participants in the first imperial "political-diplomatic-trade-scientific-military expedition" to Turkestan, which included a professional photographer:

“Upon our arrival, they [the inhabitants of Khiva and Bukhara, where the expedition stopped] initially looked at the camera almost with horror, and the photographer himself, especially when he covered his head with black oilcloth when stopping the instrument, was regarded purely as a magician. However, as they saw no harm for themselves and received their images almost instantly, the Khivinians not only got used to the camera but even asked for portraits themselves.”

Similar to photography, the text presents an outsider's perspective, which cannot be entirely trusted, and one expressive incident should not be mistaken for a pattern. Moreover, in the Western world, photographic technologies might have also seemed magical to their consumers. However, can it be asserted that for the residents of Central Asia, portrait photography has also functioned as a democratic tool for the representation of status through space and attributes?

Right: Julius Weidenbaum. Two Merchants, between 1911 and 1917

Comparing these two photographs clearly reveals the transposition of European practices into the Central Asian context and the problems this creates. On the right, in the image of two merchants, the setting is natural for Western European and Russian imperial society of that time. On the left, the photograph appears deliberately careless, presenting the image of the Other artificially, without any adaptation.

– In Western photographs, books served as attributes denoting education and wealth, as reading was accessible only to those with sufficient free time. The use of similar chairs and tables, uncommon in Central Asian daily life, makes the situation even more absurd in these photographs. The dagger in the hands of the khan is positioned militantly and threateningly, showcasing bravery and fierceness.

– The khan's costume displays regalia, aligning with the European tradition of capturing rulers of that time. It appears that depicting the body of the Other in a European manner was an important task for imperial photographers.

– Backgrounds with landscapes, including "oriental" ones, provided Europeans who could not travel themselves with the opportunity to at least connect with distant cultures and capture their fantasies. The khan, however, is photographed against the backdrop of a carpet—an attribute that over time became part of the recognizable "oriental" set, including daggers, musical instruments, elements of material culture, daily life, and national attire.

To present viewers with an "exotic aborigine" from the fringes of the empire, the shot snatches the model out of the social environment. The Other falls into the trap of the perceptions of Western photographers, who, through attributes, emphasize its bizarre features and constructed differences. While in 19th-century Western Europe, the portrait served as a means of self-identification and a calling card, portraits of Central Asians, devoid of voice or choice, became the outcomes of the fantasies of European and Russian photographers.

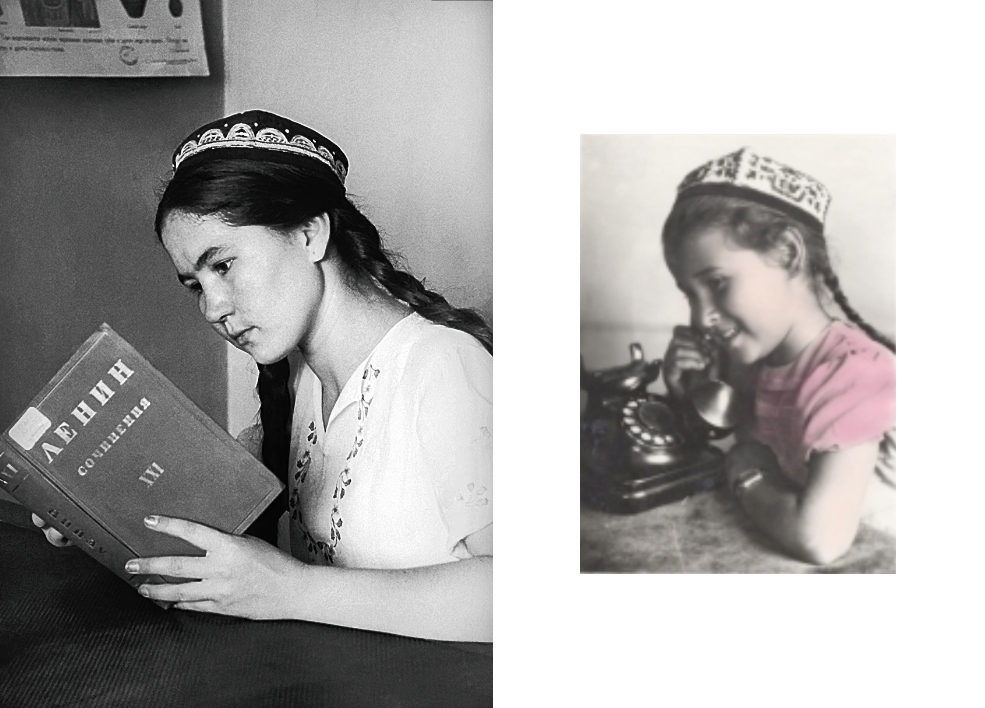

Right: Girl in a tubeteika. “Soyuzpechat.” Postcard, “Stavropolskaya Pravda” publishing house, Kislovodsk, 1950s

During the Soviet era, photography became a tool for significant societal transformations, assigned the role of creating perfect illustrations of ideological models and new myths. Photography, along with visual media such as posters and brochures, provided a means for visually highlighting the contrast between the “backward” and the “progressive.”

Despite an approximate twenty-year difference between the photographs on the left and the right — the first taken in the 1930s and the second in the 1950s — the propaganda-imposed image persists and continues to be reproduced.

– The tubteikatubteikaa Russian word for many varieties of traditional Central Asian caps., symbolizing belonging to Eastern peoples, holds special significance, particularly when worn by a woman. Soviet propaganda aimed to portray a woman without a paranjaparanjaA traditional Central Asian robe for women and girls that covers the head and body.

, presenting it as a symbol of oppression, backwardness, and primitivism.

– The mere act of a woman reading also signifies her new status. The book becomes a symbol of gender equality, accessible education, and an attribute of the “emancipated woman of the East.”

– A girl in a tubeteika, holding a telephone receiver, can also be interpreted as a message about the development of “backward” culture.

Right: From the photo archive of Faina Yunusova, 1997

Following the collapse of the USSR, in the everyday life of the newly independent state, Soviet propaganda symbols intertwined with post-colonial and post-capitalist realities. The first photo was taken only two years before the second, but comparing them reveals the struggle between different ideologies and legacies in post-Soviet Uzbekistan.

– The first photo replicates the popular Soviet image with a telephone receiver. However, by 1995, the receiver was hardly perceived as a symbol of technical progress; instead, it became a standard element of urban everyday life.

– The scene in the background of the first photo refers to a Soviet animated film that was no longer popular at the time of the shoot. This may be a nostalgia for the recent past or the photographer's careless decision not to update the props.

– Overall, it seems that the photoshoot for the first image was not aimed at creating the “best” image of oneself. Instead, it appears to be a mechanical and not very neat continuation of a ritual that originated in the Soviet context.

– In the second picture, the Soviet past can only be recognized by the bow, an attribute of Soviet-style celebrations. The rest of the attributes are antagonists of Soviet culture: a new shiny plastic bicycle, Donald Duck, and a monkey from American Disney cartoons.

Nowadays, outfits and attributes suitable for “dressing up as locals” are increasingly appearing in tourist photos. Although Uzbekistanis rarely wear such clothing in everyday life, supposedly authentic props (often made in China) are offered for photo sessions. Photos in “authentic” costumes are in high demand among tourists, and these “original” costumes are produced solely for tourist needs. As Edward Said writes in “Orientalism,” the Other, falling into the colonial trap, is forced to conform to external expectations, producing and using elements—attributes of the “imagined East.” Residents of Central Asia, from small shop owners to employees of state museums or tourist complexes, reproduce others' perceptions of themselves, adhering to the canons that emerged in imperial-colonial photography.

In the series by Tashkent photographer Hasan Kurbanbayev, on the contrary, Uzbek women themselves experiment with attributes and backgrounds. The photographer focuses on the “naive,” in his words, infiltration of symbols and signs of Western culture into Uzbek everyday life, and the comical metamorphoses of contemporary Central Asian existence.

But here, symbols of oppression that construct trap-like images for the Other are reimagined as replicas in a complex dialogue of various systems influencing the residents of Central Asia. And perhaps, the meanings of all these symbols are overturned when used outside Western European contexts, and the power over the message lies with the oppressed.

This text was originally published in Russian by Beda Media and was translated into English for EastEast by Lisa Smirnova.

List of books and articles referenced in the text:

Вальран, В. (2022). Советская фотография. 1917–1955. Liter.

Honnef, K. (1997). Deutsche Fotographie: Macht eines Mediums 1870-1970; Köln; DuMont Von der Realität zur Kunst: Fotografie zwischen Profession und Abstraktion.

Beyme, K. (2008). Einleitung: Vom Exotismus und Orientalismus zur „Hybridisierung “und Kreolisierung “im Verhältnis zur Dritten Welt. In Die Faszination des Exotischen. Brill Fink.

Eves, R. (2006). "Black and White, a Significant Contrast: Race, Humanism and Missionary Photography in the Pacific." Ethnic and Racial Studies.

Drabinski, J. (2019). Frantz Fanon.

Edward W. Said. Orientalism.

Kandiyoti, D. (2007). "The Politics of Gender and the Soviet Paradox: Neither Colonized, nor Modern?" Central Asian Survey.

Spivak, G. C. (2003). "Can the Subaltern Speak?" Die Philosophin.

Kassenova, N. and Rukhelman, S. (2019). The Thorny Road to Emancipation: Women in Soviet Central Asia.

Appadurai, A. (1997). "The Colonial Backdrop." Afterimage-Rochester New York

Barthes, R. (1985). Die helle Kammer: Bemerkungen zur Photographie. Suhrkamp.

Krafft, H. (1902). A travers le Turkestan russe. Hachette.

Pitchford, S., & Jafari, J. (Eds.). (2008). Identity tourism: Imaging and imagining the nation. Emerald Group Publishing.

Hertlein, A. (2010). Repräsentation und Konstruktion des Fremden in Bildern. BIS Verlag