On the eve of Georgia's elections, EastEast is publishing an essay by the researcher Evelina Gambino and accompanying visuals from photographer Jess Gough. The duo traveled the country, cataloging the infrastructural failures (both glaring and hidden) in their varying states (some forgotten, others liminal). In doing so, these projects and their affiliated structures reflect the current government's (and those of the recent past) "ruinous search for opportunity," and their seeming indifference to the country's population.

Travelling across West Georgia, unfinished infrastructures are everywhere. Unfinished-ness means different things: sometimes it’s filled with the bustling of opportunity, other times it indicates failure or else the precarious aftermath of a victory. Quite often these different states coexist. Contrary to what might first appear, unfinished-ness is a lively state and, often, it borders permanence. In the spring of 2023, photographer Jess Gough and I set out to document the lifeworlds that populate unfinished infrastructures across West Georgia. We wanted to register life in the aftermath of these projects; the marks that their seemingly endless repetition has left on landscapes and their inhabitants, but also the flourishing of activity in the wake of failure.

In traveling from one infrastructure project to the other—from a failed port, to a hydropower plant that had been halted after a popular uprising, to a highway under construction and another permanently congested—we experienced how infrastructures and ecosystems of different kinds have become entangled. The liveliness of infrastructures and the harm they impress on their surroundings exist in a symbiotic relation and, perhaps more poignantly, as accretions of previous projects. Nikhil Anand suggests that “infrastructures accrete. They gather and crumble incrementally and slowly, over time, through labor that is at once ideological and material.” Infrastructures are seldom built from scratch, yet they are often cast under an aura of opportunity. Georgia’s recent past is framed by a ruinous search for opportunity. In the present, the social, material, and ecological lives of missed infrastructural opportunities populate the landscapes we traveled across. Echoes of these failures travel beyond these sites to permeate the country’s politics.

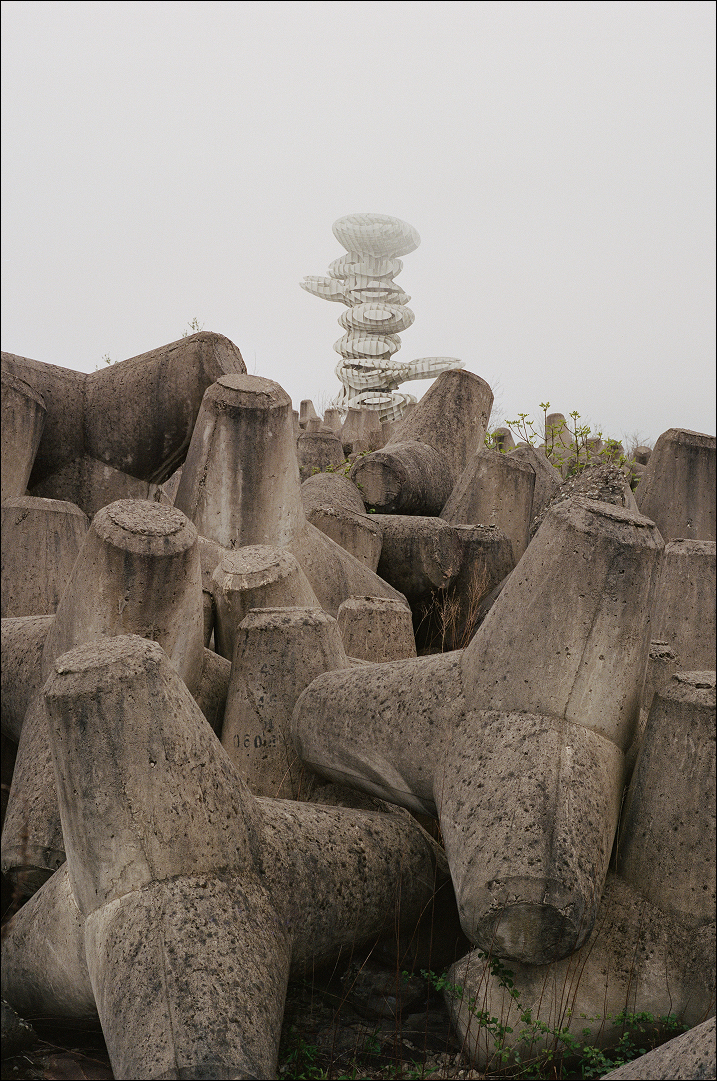

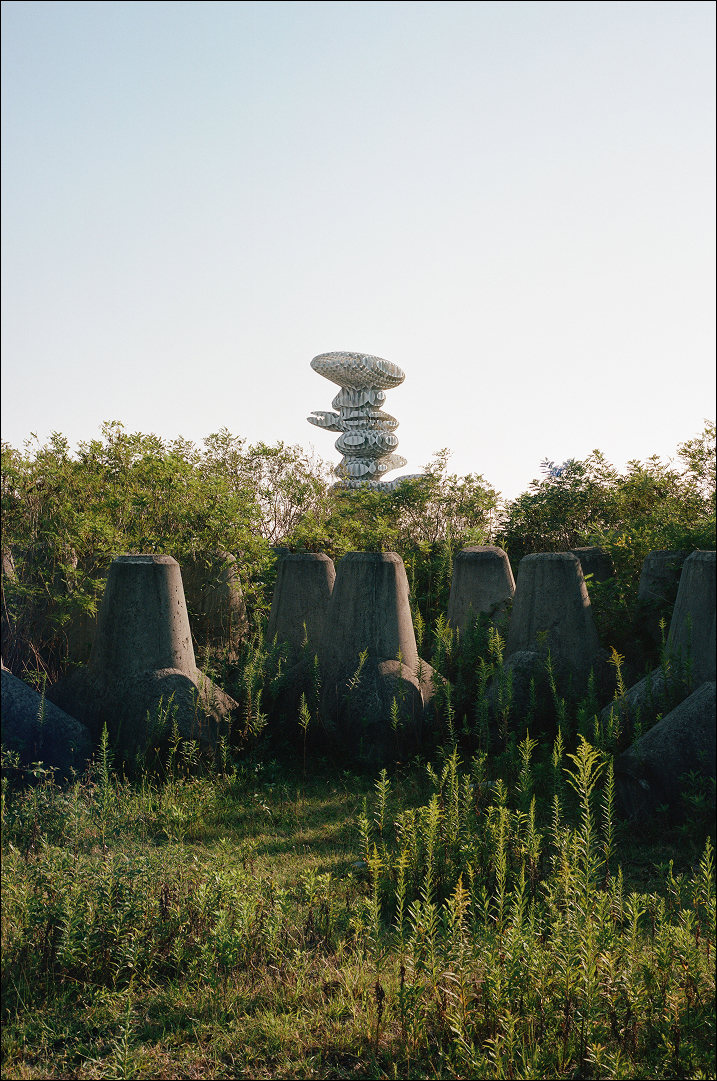

Embodied in infrastructure, opportunity becomes a material gamble on the future. Not paying off, it has nevertheless given rise to a cycle whereby each infrastructural project disavows previous failures, extending the horizon of payback just a little further. The word opportunity comes from the Latin opportunus: ob- "in the direction of" + portus "harbor," originally describing the wind driving towards the harbor. It seems fitting thus, that amongst the not-yet infrastructure we visited, one feels emblematic of this ever receding promise: the port of Anaklia. This port was known as the project of the century, until its abrupt interruption during the initial stages of its development in 2019. The project’s failure left much of the country in shock and the inhabitants of the village neighboring the port to contend with the large transformations left behind by the attempted construction. Two hundred hectares of empty land running along the sea split the village in two. For several months after the construction was halted, inhabitants had to circumnavigate this no man’s land, still fenced off. Now a makeshift road has been carved into the mound of reclaimed sand that rests on this territory to allow people to travel across it.

As we reached Anaklia, several years after the port’s failure, I remember its depiction as both an exceptional and predestined development. Yet, from the standpoint of its debris, the window of opportunity attached to the port shows itself as always, already an afterlife. One characteristic of unfinished infrastructures across Georgia is that they are seldom put to rest. Despite its much discussed failure, the ongoing attempt to build a port still looms over the village of Anaklia. As recently as May this year, the Georgian government announced that a new consortium, this time Chinese, has been selected and that works for a new port are expected to start in the early autumn.

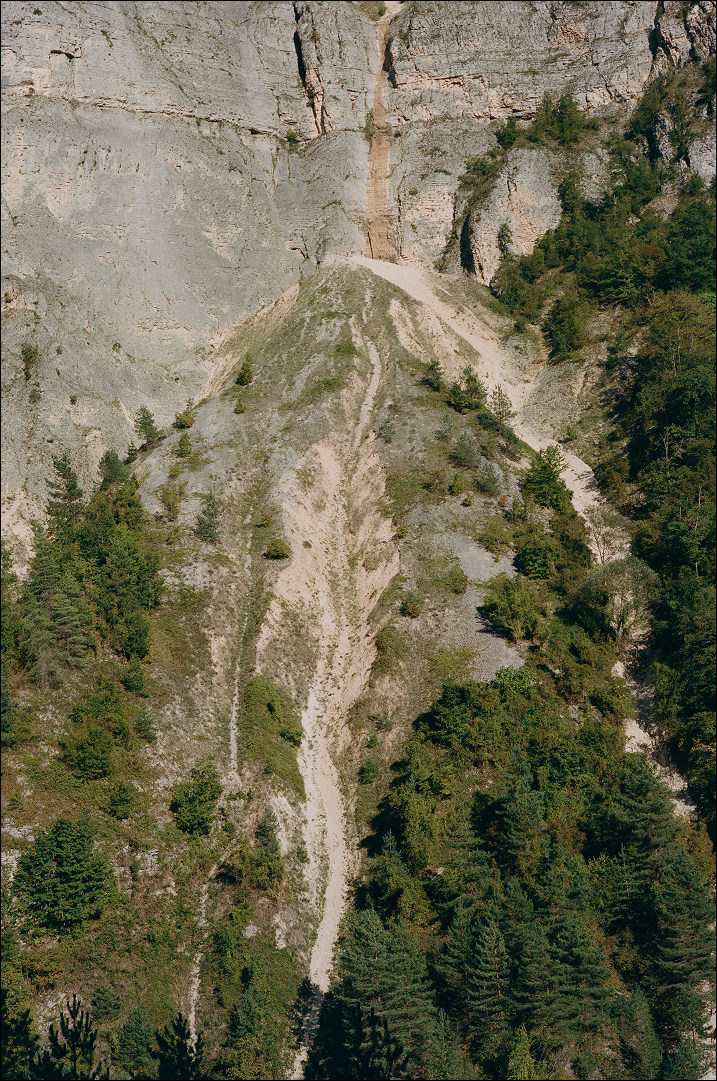

Across the country, new and old infrastructure projects overlap as ceaseless repetitions of the same developmental dreams. Becoming a busy logistics hub has been Georgia’s goal since its independence from the Soviet Union, yet at the junctures of this transit ambition chaos prevails. The Georgian Military Road that stretches from Tbilisi to Vladikavkaz is the only artery connecting Georgia and its southern neighbors to Russia. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 has forcibly rerouted a notable portion of cargo through this narrow high mountain road causing trucks to queue for up to a month to be processed at the border in Lars. Traveling up and down this road, Jess and I met those caught in this almost permanent bottleneck: stuck on the side of the road, often without basic necessities, truck drivers are forced to relieve themselves in nature, sometimes for weeks on end, while the inhabitants of nearby villages are stuck in traffic or at home inhaling the fumes produced by the queue of cars.

Traveling up the highway towards Stepantsminda, one of the most popular tourist destinations in the country, at the feet of Mount Kazbeg, the people we spoke to were angry and disheartened. Along the road informal ventures have mushroomed: new truck parks dot the highway, and businesses previously targeting tourists turn to cater to truckers. If this was always the plan, how can the country be so unprepared? Indeed things have not gone as imagined: not just the ongoing invasion but the frozen conflicts at Georgia’s northern borders increase the pressure on this singular road. Yet the chaos cannot be ascribed only to geopolitics. For years on end infrastructures have been projected as vehicles for attracting financial investment rather than public goods necessary for the smooth, or at least, humane, running of the country’s life. The effects of this repeated mistake keep being discounted on those who live and work along the military highway.

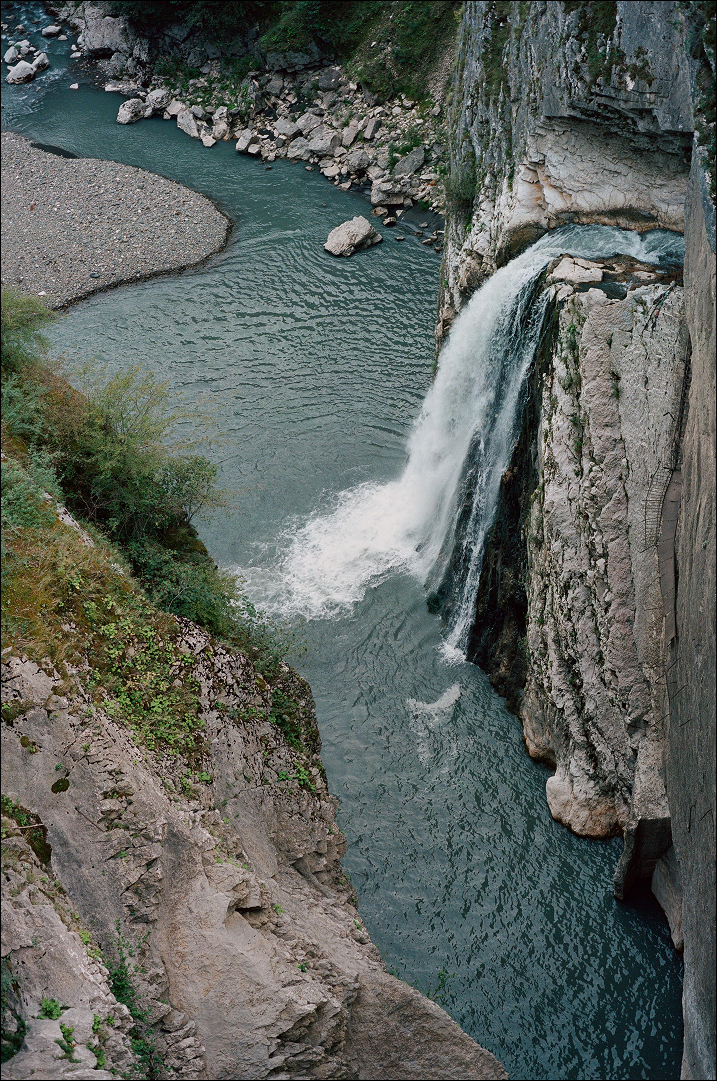

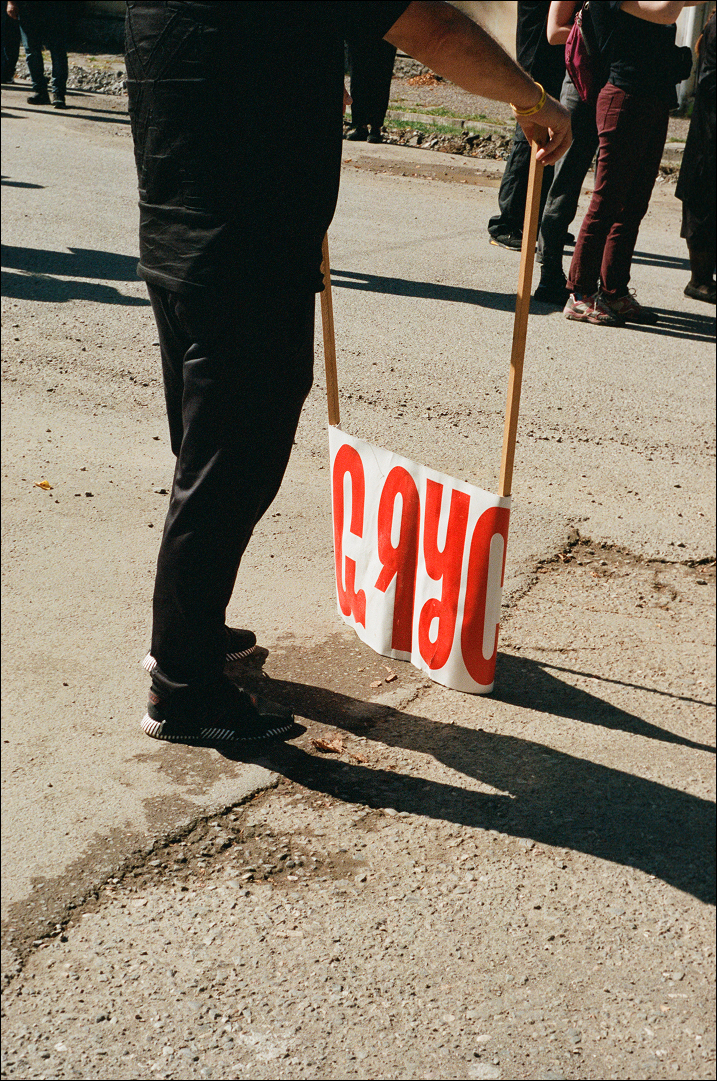

The present is increasingly marked by a sense that the world we were modernizing towards does not exist. The costs of clinging to that world are inscribed into the earth, everywhere. Yet most attempts at addressing our planetary problems trace the same paths, deepening their marks onto landscapes and ecosystems, and efforts at doing things differently are crushed. This is made explicit in the Rioni Valley where the project to build one of the largest dams in the country has been halted after years of opposition by locals and their allies. Controversies around infrastructure are always heterogeneous, and like many other similar movements across the world, the struggle to save the Rioni valley rested on an awkward alliance between people fighting displacement: environmentalists, nationalists, Christians, and others. Uniting these disparate and often conflicting identities is a concern for the potentially disastrous impacts of the dam on its neighboring ecosystems and a sense of exhaustion with living in the wake of infrastructure’s promised and ever delayed prosperity.

In opposing the dam, the villagers of the Rioni Valley proposed an undoing of the larger developmental project that provides a rationale for its construction: the plan to transform Georgia into a “green energy” hub for the region by tapping into its bountiful hydric resources. This vision promises economic prosperity and energy security, in compliance with the global commitment to a more sustainable kind of resource extraction. But who gets to decide where the boundaries of sustainability lie is a political question. The inhabitants of the Rioni valley are not alone in pointing to the unsustainability of the country’s developmental trajectory. In the last decade, large infrastructure have become the catalysts of a growing and heterogeneous movement. From the anti-dam uprisings across mountainous regions, to local campaigns against the unbounded privatization of nature, protestors have joined forces to oppose projects that place infrastructure at the service of profit over populations and environments.

Across the world authoritarianism is brought in as a solution the accreted effects of years of market-driven projects. The events of the recent months in Georgia speak of this reactionary politics. After months of protests, on the first of August 2024 the government succeeded in passing the so called “foreign agent law.” The law dramatically curtails citizens’ and non-governmental organizations’ ability to challenge the state by effectively banning foreign-funded organizations from participating in public life. Dubbed by many as a sign of the government’s authoritarian turn, this law is not directly focused on infrastructure, however, it cannot be separated from the years of infrastructural undoing that have marked Georgia’s recent past. In the aftermath of the conflict over the Namakhvani dam, links between protest movements have strengthened and protestors have been moving across regions to support each other and build new campaigns. From the mountains to key industrial sites like the manganese producing town of Chiatura, locals have been blocking roads, organizing encampments and forcing the cancellation of contracts. Marking most civil society groups as foreign agents, as the new law proposes, is likely to suppress those voicing an alternative vision of infrastructural development and cast a veil over infrastructural failure. But these laws, perhaps paradoxically, can also be seen as a tacit acknowledgement that the desired transformation of the country has failed. Faced with a chance to learn from this failure, however, the government has decided to bulldoze through it: forcibly superimposing new projects on ever more broken foundations.

All photos courtesy of Jess Gough