Shuhrat Saadiev, CC BY-SA 3.0

On the eve of the winter holidays, we asked some of our authors how they celebrate the New Year and how it’s done in their homeland. Ikuru Kuwajima, Jenia Kim, Gabriel, Bermet Borubaeva, Kamilla Akhmedova, and Kamila Rustambekova told us about their favourite New Year dishes, songs, movies, and warm rituals.

Ikuru Kuwajima

The New Year is one of the most important holidays in Japan. Though I haven’t been there since 2003, I believe nothing has really changed. The festive mood arrives even before the holiday itself. Generally, it’s a family holiday, so many people stay home on the evening of December 31st. The dinner that is served is fancier and tastier than usual, with sushi, sukiyaki, and sashimi. Closer to the New Year, the most active people head to the temples to hear the ringing of the New Year’s bell. Some go up into the mountains to watch the first sunrise. But the majority quietly sits at home with their families. They often watch TV, especially KōhakuKōhakuThe annual New Year's Eve television special Kōhaku Uta Gassen has been on air since 1953. It started as a radio program in 1951.—the singing contest show. When midnight strikes, everybody eats soba noodles in hot soup.

Then there are usually at least three days off. During this time people often go to temples and buy omikuji there—paper strips with predictions for the upcoming year. Adults give children money, this custom is called otoshidama. People exchange New Year’s greeting cards, nengajo.

Photos by Eliazar Parra Cardenas, Teruhiro Kataoka, Vincent Van den Storme / flickr.com / CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

The traditional New Year’s food is osechi ryori—a set of different traditional dishes in a multi-layered box. It's a bit like a giant bento. Recipes differ slightly depending on the region, but usually, these boxes contain baked fish and shrimp, mashed sweet potatoes with chestnut (kurikinton), rolled omelette (datemaki), sweet black soybeans (kuromame), marinated herring roe (kazunoko), boiled fish wrapped in thick kombu seaweed (kombu-maki), grated pickled daikon and carrots (namasu), and boiled shiitake mushrooms. These dishes are difficult to cook in Russia because it’s hard to get all the required ingredients here. You can find sweet potatoes and chestnuts in Moscow sometimes, so theoretically you could make kurikinton, but the taste of the local sweet potato is very different from the Japanese one. It might still taste good, but I haven't tried it. But grated pickled daikon and carrots (namasu), of course, can be cooked here: you need to grate or thinly slice carrots and daikon, put them in a bowl, add salt, and leave them for 10 minutes. Then add vinegar, a little sugar and soy sauce—that's it.

During the New Year holidays you can often hear folk songs and traditional music in the street, in stores, and on television. Older Japanese like watching the New Year’s film series It's Tough Being a Man. Between 1969 and 1997, a new movie was released almost every year but I hardly ever watched these movies myself. It seemed a bit too old-fashioned to me . . .

Jenia Kim

We celebrate both the New Year on December 31st and the Korean New Year—that’s what we call the Lunar New Year. But December 31st is more important for us. Like most people in Russia, we always gather together as a family and cook various salads: Olivier saladOlivier saladA salad dish, traditionally served during New Year Eve's celebrations in many Post-Soviet countries., dressed herring, kholodetskholodetsAspic, a jellied meat dish of traditional Russian cuisine.

—all the New Year's classics. In addition to these, we also serve Korean dishes: kim-chi, which we eat all year round like bread, some special salad, fernbrake, and marinades, such as pickled cucumbers with garlic.

There is no special New Year’s dish, but we have a special hangover dish for January 1st: cold nyangugi soup. I think it may be useful for many readers. It is made of water and soybean paste, chopped vegetables, and dressed with different spices and lots of vinegar. This slurry is eaten with hot rice, and it actually saves you from a hangover. Here is how you cook rice.

1 liter water

1 ½ tbsp roasted Doenjang (soy paste)

1 tsp salt

2 tbsp sugar

1 tsp vinegar (70%)

Half bunch cilantro, chopped

Half bunch green onions, chopped

2-3 cucumbers, diced

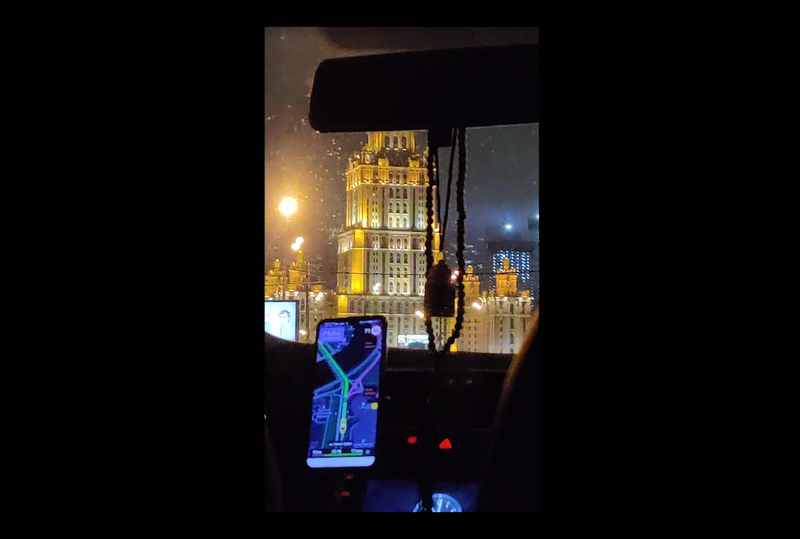

For me, this day differs from the others in that I watch a lot of TV because I usually celebrate the New Year with my family and with them everything is traditional. We turn on the TV and watch all the Russian New Year’s movies: Moscow Does not Believe in Tears, The Irony of Fate. Every year we watch the same thing. Then we put on some concert, an absolute classic. We live in a cottage community where the program is basically the same. At midnight, for years running, we listen to Putin’s speech, then we go to watch fireworks, after we return we sit and chat for some time and then go to bed. It's rather boring, but it's the kind of a family holiday, a tradition. I also have a little brother, we entertain him with games he receives as New Year’s presents, so we can assemble legos, puzzles.

Gabriel

The New Year is one of the most beautiful holidays of the year. Despite different folk and religious calendars, people all around the world have been able to agree that January 1st marks the first day of the year for most of them. The special meaning and magic of this date are also in the way you celebrate it, what traditions accompany this festive moment. People travel all around the world to get closer to their family, or just in the right festive place. There are plenty of different ways of celebrating, but everything is done for one thing—to make the celebration beautiful and cosy.

A few years ago, when I was still living in Cameroon, I always spent that moment in my hometown with my family. BecauseI was serving in a different place, I sometimes had to travel right before New Year's Eve to get home in time for the holiday preparations with other family members. It was always an extraordinary moment because we would gather as a family for dinner to celebrate the arrival of the New Year. As a member of a Christian family that believes there is nothing more beautiful than to celebrate the New Year in church, I can say that this is our main family tradition. Minutes after the New Year, we returned to the family circle to have some barbecue—roasted corn, fish, and plums. Alcohol enlivened the evening in anticipation of the real celebration that was coming the next day.

When the morning came, kids would go from house to house, offering flowers and greetings to adults in exchange for small coins. Women would start cooking, and men would be setting up tables and chairs. As for me, being a food lover, I tried to stick around women and the kitchen, hoping to taste various dishes before they would get on the table. That day at the holiday table you could find various traditional foods and in my region we always have plenty of pistachio dishes, sweet potatoes, and local needle beans. Especially these small beans because they don’t grow anywhere else and are quite easy to cook: you just boil them for two hours, then fry them in red palm oil and they are done.

Usually, on the first day of the year, the doors of apartment buildings are open to everyone. Neighbours visit each other, wish all the best, and have some treats. After the family meal, you can go about your business, some prefer to meet friends and given that the city is small, everyone knows each other, others stay home and watch Christmas movies and TV shows. In general, it’s never boring.

When I moved to Russia a few years ago, I was honored to celebrate with my Russian friends and learn more about local traditions. The context changes already because families here are not as big and many people celebrate with friends, that’s how it was at the last two New Year's parties I had with my Russian friends in St. Petersburg. The cool thing here is that people give each other gifts—I liked it very much.

The New Year itself is very important, so here they cook a feast for the occasion. I adore salads so I really enjoy Russian cuisine, as it offers a huge variety of salads at the New Year's table. After the meal everybody exchanges gifts, then we watch New Year’s shows or play board games. As I am a foreigner, everyone pampers me like a little child and it feels very nice to have all this special attention and willingness to share the culture with me. In the morning we disperse.

This year I will probably celebrate with the guys we rent an apartment together. COVID-19 leaves no chance of going to my friends in St. Petersburg like I did previously. We'll just gather as roommates. We are all from different countries, but we'll try to be united, have a little party, spend New Year's Eve together. I don't think it will be anything special, but it's always magic, even without preparation.

Kamilla Akhmedova

In addition to the usual New Year, Uzbekistan also celebrates Nowruz. This tradition is a thousand years old and has its origins in the Zoroastrian religion. It is celebrated on March 21st: on that day we have an official holiday and folk festivities. Some time before the holiday, khashars are organized in the yards—it’s when people from the whole yard or mahalla unite to clean the common territory. They sweep the streets, paint trees and old houses, and fix things.

Usually, we cook plenty of traditional dishes on Nowruz: pilaf, samosas, spring salads, but the most important dish is sumalak. It's something like peanut paste but made of wheat. To be honest, I personally do not find it tasty (although many will disagree with me), but I really like the tradition of cooking it. Sumalak is boiled for a whole day (most often it’s done by women) and while stirring they make various wishes. Sometimes they put pebbles in it: legend says it brings luck to those who find it. When you participate in such ceremonies, you feel like a tiny piece of a big history that was created long before you existed.

I also love it when neighbours give each other some delicacies, as a gesture of courtesy and respect for one another. We do it not only on Nowruz, but on all the holidays we celebrate in Tashkent. For example, during Hait, Muslims can treat Christians (or any other people) with pilaf, and at Easter Christians treat their neighbours with kulichi. It is a great uniter.

On Nowruz evening they usually give concerts in the Palaces of Art and also broadcast it live on local television. A lot of people with flags dancing and singing on stage. There’s a song by Yulduz Usmanova called O'zbekiston that I associate with such concerts (not necessarily with Nowruz).

Kamila Rustambekova

Nowruz is one of the symbols of Uzbek culture; it is always a very bright and eventful occasion. I remember how my grandmother took me to the city square on this day as a child. It is a very bright memory from my childhood: a big stage, performances, national dances, a fair, and the most delicious part: many tables with all kinds of dishes, sweets and, of course, different types of sumalak.

Making sumalak is a whole collective ritual. Starting early in the morning, neighbours of one makhalla gather in someone’s yard and start cooking—it’s always accompanied by loud music, songs, and dances. Sumalak is stirred with a large skimmer for more than ten hours, so practically all the mahalla’s locals have to be involved. Each family makes its small contribution to the common cause, it establishes and develops ties between local residents. If sumalak is cooked properly, it has a very sweet taste, although no sugar is added to it.

People throw pebbles on the bottom of the cauldron and make wishes: in a practical sense, these pebbles help in stirring the sumalak and prevent it from sticking. Also, there is a tradition of interpreting the pattern formed on the surface.

The history of these rituals is very interesting—there is a belief that long ago there lived a single mother with seven children. Once a poor harvest year happened and they were literally starving. When her children’s lives were hanging by a thread, to cheer them up she said she would cook something tasty for them. She took a cauldron, poured water in it, added the sprouted wheat she gathered in the stable and began to cook it, stirring continuously. She threw pebbles inside, saying that it was meat. In the morning she fell asleep for a few minutes, and when she awoke she saw that the cauldron was full of a warm chocolate-colored mass with wings pattern on its surface. Thus she realised that angels visited her house and made the dish magical. The food turned out very tasty, and the woman shared it with all her neighbours who were also hungry. That is where the tradition comes from. In addition to sumalak (the star of the holiday), we also cook green samsa (kuk somsa), pilaf, and put the sprouted wheat on the table.

Bermet Borubaeva

Now in Kyrgyzstan we celebrate the New Year on the night from December 31st to January 1st, but before that there was another, pagan New Year that greeted the arrival of spring —the holiday of Nowruz. Now the traditional New Year is an important holiday in our culture; everybody wants to complete all the tasks, make wishes, and set the holiday table with the family. A feast with family or friends, gifts, wishes, New Year's greetings from the president, midnight, champagne—surprisingly, we have all that too.

Usually, a main hot course is cooked: pilaf, manti, or baked meat or fish. Then goes a very classical set: Olivier, vinaigrette, dressed herring, tangerines, champagne, Bengal lights, and party poppers.

People mostly watch some New Year’s programs on Channel One and listen to Kirkorov and others from that crew, and watch Little Blue Light (Goluboy Ogonyok)Little Blue Light (Goluboy Ogonyok) A popular musical variety show aired on Soviet television from 1962 to 1985., Irony of Fate or Enjoy Your Bath, The Girls.