Designer Jenia Kim was born in Tashkent, but she has lived in Moscow for almost twenty years. Two years ago, she returned to her hometown to start working on a new collection dedicated to the ethnic and cultural identity of the local Korean diaspora, which emerged due to the deportation of the Soviet Koreans to Uzbekistan in 1937.

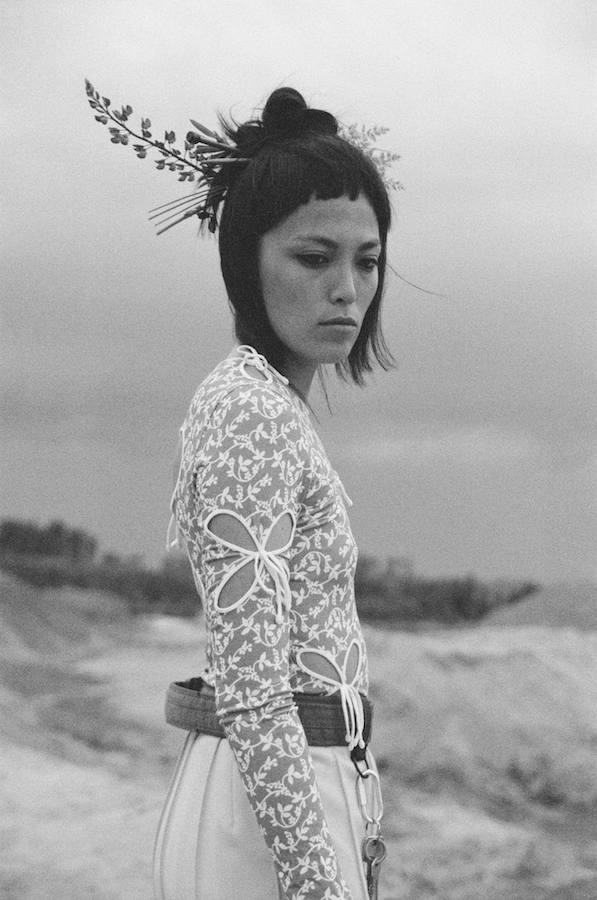

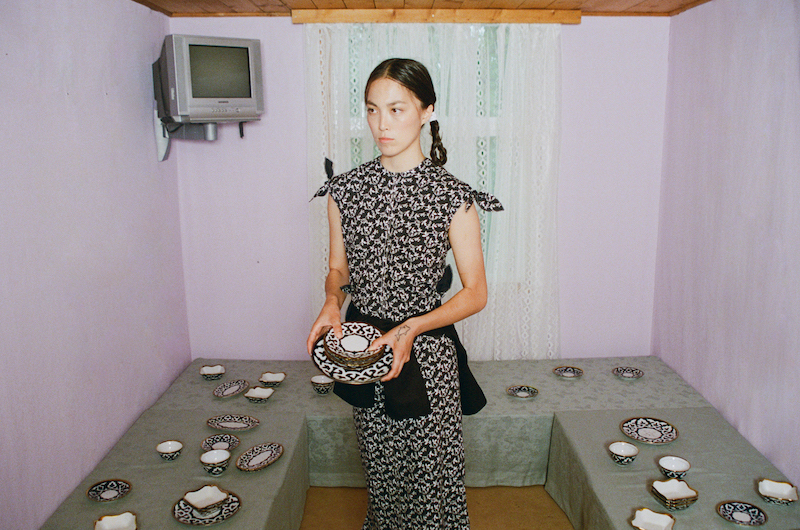

EastEast presents a collaboration between photographer Masha Demianova and Jenia Kim, in which the designer’s memories of Uzbekistan and Korean traditions are inscribed into a dreamy visual landscape. It is complemented by a conversation between Jenia and EastEast editor-in-chief Furqat Palvan-Zade, also a native of Tashkent, about the changes that have taken place in the city, the reasons for her return, and the process of creative searches and material production.

I often thought about the benches in my yard, the glass-wool-wrapped pipes along the river near the garages. The field I used to hang around in a lot when I was growing up—first playing there in the dust, making balls out of it with my saliva, and later—waving goodbyes to boys I dated. I remembered the terrible road we took roller-skating on rattling wheels, and the relief we felt when riding on the presidential highway. I remembered little bazaars where one felt like all the sellers were your family, the well my grandmother used to sit on every day, selling gum and single cigarettes and big pigodis (stuffed pies, a Korean dish popular in the Russian Far East and Central Asia—Ed.) that we ate during our school breaks. I also remembered taxi drivers in white Nexia, Damas, and Matiz cars, narrow streets with low houses, melon and watermelon on the tapchan (a type of outdoor furniture popular in Central Asia, it combines a large bed capable of holding up to eight adults with a table for meals—Ed.).

The most vivid memory of my childhood is Broadway (a pedestrian street in the center of Tashkent—Ed.). On almost every day my mother had off, we used to go to the Alisher Navoi Theater and then take a walk along it. For me, those outings always felt like little holidays. The street was full of artists and street cafes with oilcloth curtains at the entrance, at cafes my mother got roses as presents, and on our way home we bought trinkets.

I was also very much surprised to meet local creatives. I returned there a completely different person, you know, eager to discover some like-minded people. And the chances of finding those treasures around the city turned out to be rare. There were not as many creative people as in Moscow. I was very excited to get to know everyone who had something to do with any kind of creativity—because one needs to have a strong spirit and a love for art in order to develop something there. First, I was very impressed because I had little hope that I would meet someone, but six months later I realized how sad the situation actually was and how much the city was suffering from cultural stagnation.

Once I failed to hold my tears when passing by another plastic building. I really hope that someone will be able to stop this, and people in power will see the beauty of what belongs to them. This is largely why I have chosen dowry as the topic of my collection: I wanted to show that a modern collection can be made of Uzbek materials and techniques. I truly believe it is beautiful.

First, I found an embroiderer who gave me the contact of a woman who dyed fabrics. Then I traveled across Uzbekistan—to Samarkand, Nurata, and Angren—searching for good tailors. I used Nexia cars to move around—well, not so comfortable, but very memorable, I should say. Then I started sewing my collection at a production facility that a friend of mine had suggested, but we failed to find a common language. I started looking for tailors again—this time through OLX (an international online service that provides spaces for ads.—Ed.), called numbers I found in ads. Setting up the process took me about six months. There are still a lot of difficulties, but I see the progress. Now everything works like this—in the workshop or with homeworkers I make technical drawings and embroidery patterns that are sent to Angren and Nurata, pieces are then sewn in Tashkent or Moscow. Well, I should say I still do not know where I want to be based, so there is no permanent production yet.

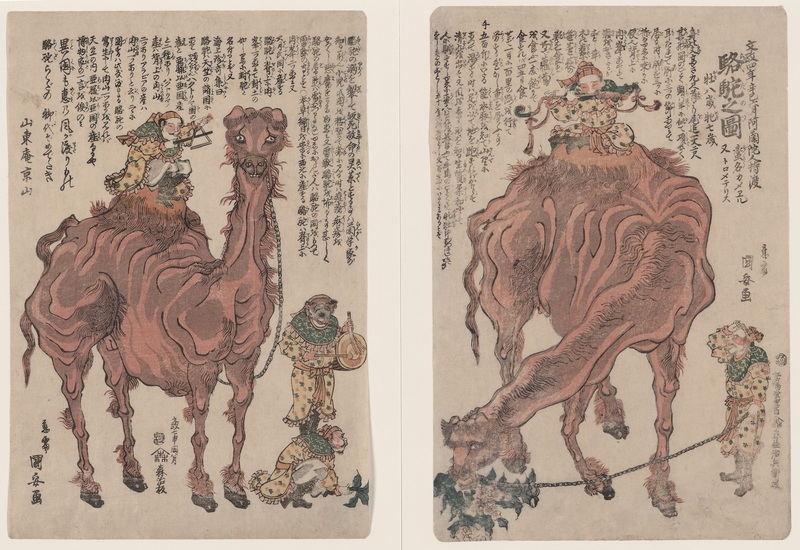

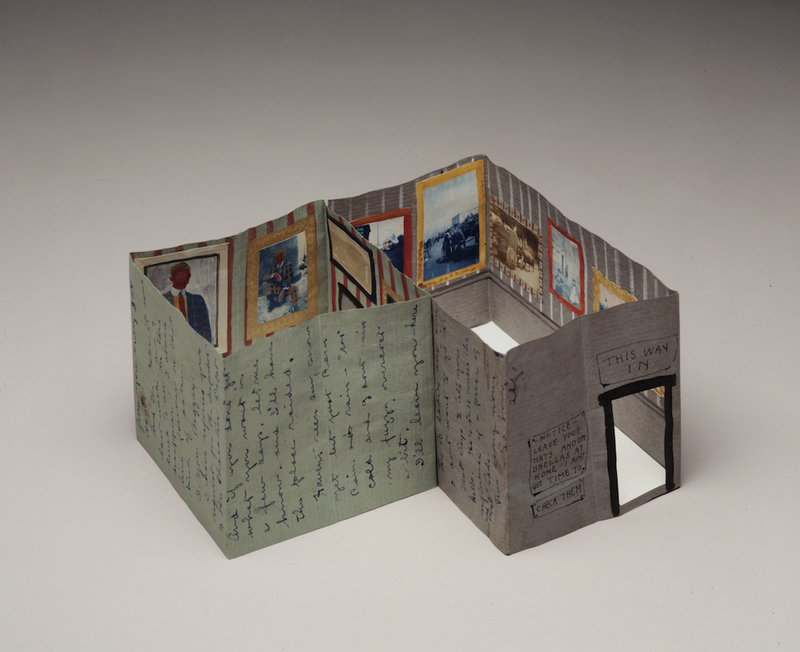

Through these photos, you can feel the life of Koreans at different times and trace the path that brought them to Uzbekistan, where their life became a series of feasts at which numerous stories from the past and present are discussed.

Сredits

Creative direction: Jenia Kim

Photography: Masha Demianova

Style: Stacey Batashova

Hair and makeup: Julia Rada

Model: Yumi @ UTRU Talent base

Production: Svetlana Bevz

Production assistant: Elizaveta Dmitrievna

Photography assistant: Paul Lehrer

Special thanks to Ivan Markovich

All clothing J.KIM

Translated from Russian by Olga Bubich