For two years Mari Bastashevski sailed between key global logistical hubs on container ships, from Istanbul to Shanghai, Los Angeles, Pussan, Hong Kong, Athens, Colombo, Nairobi, Dubai, Singapore, Kampala. This is how her project 10,000 Things Out of China unfolded, circumnavigating the world by sea in order to explore the way this world is being produced. “Ten thousand things”—wan wu 万物—is an ancient Chinese concept describing everything that exists, all things on earth, the universe itself.

In her essay for EastEast, Mari Bastashevski muses on their rhythms and tides. We are showing the full video along with selected photography from the project, which has been shown as a solo exhibition in Groningen, Freiburg, and Montreuil.

I have always been fascinated by those people who, faced with a world so full of horrors it can seem intolerable, claim that the human condition is unchangeable, that nature is a monstrous machine, that humanity has produced an endless cycle of inhumanity even when animated by good intentions, and then back away. The problem is not what other people do to you. The problem is to stand impotent before the horror that afflicts the majority of people, the most precarious of our fellow human beings. Every day we find ourselves faced with the intolerable, and no promise of utopia—whether it be political, religious, or scientific—is capable of calming us. Each generation is obliged to verify this horror anew for itself, and to discover that it is impotent. So either you take a step forward or you take one back.

Elena Ferrante

We beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.

F. Scott Fitzgerald

A port is a node in a polytemporal network. It is a site where rhythms connect, interpenetrate, are submerged and disperse. In the port of LAport of LAMy field research trip in LA took place shortly before the inauguration of Donald Trump. While President Trump was accusing the Chinese government of either carrying out or fabricating (for profit) every man-made disaster in history, Shenzhen officials were being given an official tour of the terminals in Los Angeles accompanied, on a luxurious yacht, by the CEO of the port, Gene Seroka, along with US officials and other distinguished guests. The Los Angeles terminals share this landscape with an ideologically incompatible TV series and a US federal prison, each unperturbed by the existence of the other., near the harbor, lies FCI Terminal Island, a prison compound. Visitors flow in and out of the low-security prison, different electronic currents defining their levels of access and degrees of freedom. Nearby, other rhythms are spiralling: Miramax crime TV production cameras and the pump of the crud from the belly of the Suezmax unconsciously form a polyrhythmic architecture that only sporadically forms a chord of mutual awareness. A similar constellation of institutional dynamics exists in a state of verticality in the port of Hong Kong. Again, thousands of individual and machine actions occurring, linked by rhythms that are unconscious, but felt.

iPhone parts inside a container ship cross the distance between these two ports in a matter of weeks. The users of the products can cross it in a day, depending on the rhythms to which they are subject. The commodities of cultural labor traverse a route carved out by cyber-optic cables, stretching from the CoreSite data center beneath the old LA post office to the Hong Kong Stock Market, travelling at a rate of 2.88 terabits per second. This cyber-optic fibre cable master rhythm is sustained by the infrastructure above—a rhythm it also governs—accelerating far beyond human perception. The eco-rhythm of the planet sets a limit on these transorganic rhythms through ruptures and spillages between the virtual, the informational, and the material, from networked entities to concrete architectures and physical bodies. The most recent reminder of such limits manifested itself in the colossal fertilizer explosion in the port of Beirut.

An industrial force, as Bernard Stiegler points out in Technics and TimeTechnics and TimeBernard Stiegler, Technics and Time (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1994), 37, 70, 134, and 223., is no longer coterminous with ecological boundaries. It propagates independently of all territorial considerations as it reshapes the geographical entity and its political borders. The history of techno-progress is the pas-de-deux of the ecological and the industrial. A feedback loop in which an ecology, considered a resource for the industrial, gives rise to new appetites and new forms of industry, a new eco-industrio-system. Cycles within cycles; once in a while, a cycle breaks out, creating its own ecology even as it feeds back periodically to the source that generated it.

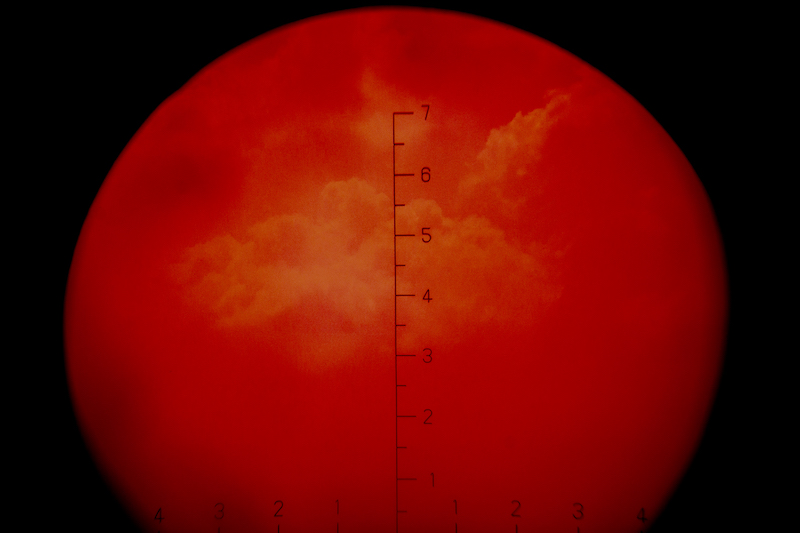

Calling at the Port of Singapore, periscope view

Port of Colombo, CCC construction site hard hat area warning

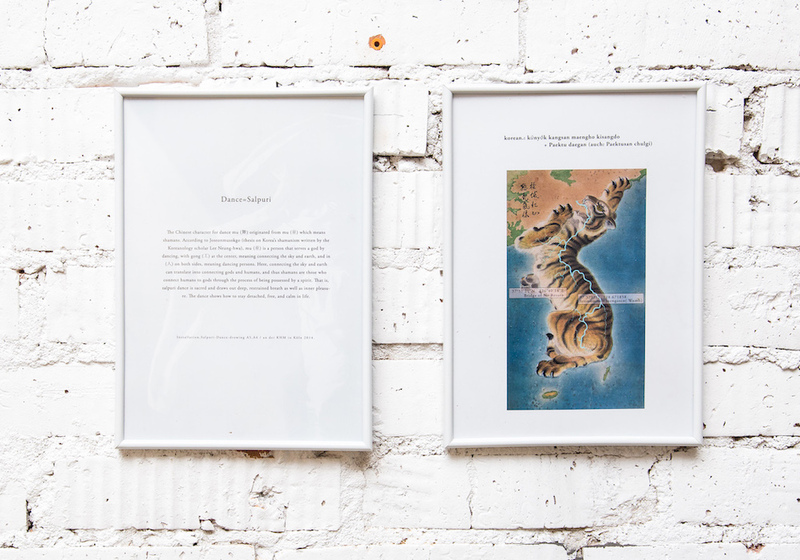

Shopping centre advert inside a rest area at the Foxconn Factory City

Director of the felting factory in Humen, China which makes patterned textiles for Zara and Victoria’s Secret

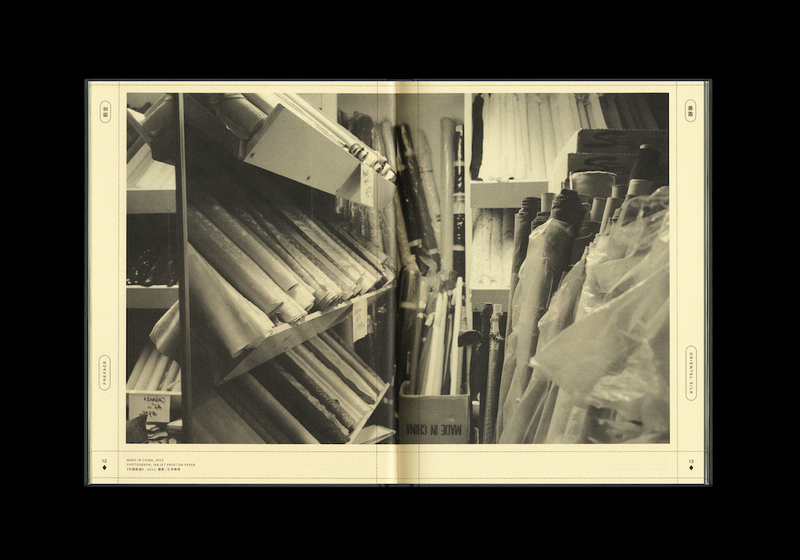

Book printing factory that counts Penguin and Disney Books among clients

Book printing factory that counts Penguin and Disney Books among clients

Book printing factory that counts Penguin and Disney Books among clients

Lunch at the Disney and Penguin Books printing factory, Saturday afternoon, Shenzhen

Foxconn Factory fulfilment centre, Shenzhen, China

Personal belongings depository, Foxconn

Coca-Cola bottling plant in Hong Kong

R&R facilities inside Foxconn factory

R&R facilities inside Foxconn factory

Accelerationists may interpret such ruptures, the Beirut explosion or the DeepWater Horizon oil spill, for example, as dry-runs for a much fetishised “terrible event.” After all, the port of Lebanon is a major logistical hub. Its collapse undoubtedly affects the sprawl of polytemporal shipping and the production network that connects to it. Terrible events come and go, it is not their speed of arrival, their revelation, their literal “apocalypse,” that matters. Speed, the idol of Futurists, AccelerationistsAccelerationistsNick Land: “Machinic revolution must therefore go in the opposite direction to socialistic regulation; pressing ever more uninhibited marketisation of the processes that are tearing down the social field, ‘still further’ with ‘the movement of the market, of decoding and deterritorialization’ and one can never go far enough in the direction of deterritorialization: you haven’t seen anything yet.” See also Benjamin Noys’ Malign Velocities: Accelerationism & Capitalism; Fish Story (1995), Shipwreck and Workers (1998-2000), Forgotten Space (2010), Titanic’s Wake (2003), and Dear Bill Gates (1999), all by Allan Sekula., and other assorted variations of prepper intellectualism is a distinct quantity from rhythm. Rhythms entail speed, but speed is only one dimension of a rhythm. As there is a difference between speed and rhythm, so there is a difference between rhythm and topological infrastructural time, and a difference between every individual life governed by a specific rhythm, the one that pumps blood through their bodies. The speed of that rhythmThe speed of that rhythmYves Citton, The Ecology of Attention (Polity Press, 2017): “The political rhythms (electoral, fiscal, fiscal) of nation-states have recently been deeply disrupted by the financial collapse of North American subprimes. Indian telemarketers have to work at night to be in sync with the availability of Western consumers. Pascal Michon is just concerned about the rhythmic implications of globalization. Resisting their perverse effects is a major challenge, which can not be satisfied with finding the rhythms of a "good old time" illusory and unrecoverable.”

is perhaps the least important aspect of its significance, or its consequences.

The event is as much about how time flows through a place as it is about a place in time

The port of Colombo in Sri Lanka exists on the same rhythmic plane as Hong Kong and LA, but this plane is penetrated by multiple temporal intersections. Colombo joins the quotidian loop of contemporary Hong Kong and LA, but it also hosts “Universal Swatch Time,”“Universal Swatch Time,”Tiziana Terranova, Network Culture Politics for the Information Age (London: Pluto Press, 2004). and offers a digested version of the ghost of 1983 to the visitors who circulate through its harbor. After its sale to Chinese Harbour Engineering in 2016, the port is also a portal of return for history. What triggers these pulsations in time may vary: a bottle of Scotch stashed away at customs control, flocks of wrens at the docks, the Grand Oriental Hotel, its meeting rooms rhythmic incubators of their own, where a visitor circulating through can rent the suite once occupied by Anton Chekov for a reasonable fee.

The adjacent Maritime Museum next to the Port Authority keeps a dusty collection of treasure maps, oil lamps, and the nets that were once used to lift elephants onto ships. A brief history of the port is explained in this institution, its take over by Dutch, then the British missions, and now the Chinese expansion* by means of three almost identical watercolor paintings. The colonial footprint in Colombo, conveyed in ironic and yet innocuous—almost naive—ways, has not yet been reformatted to fit the post and neo-colonial ideologies of the Western present, but the light nudge of history will not prevent Sri Lanka from becoming one of the first countries to already feel the impacts of the fast-approaching changes in ecological rhythms. In the words of another resident of a precarious port, Gloria Estefan and the Miami Sound Machine, who, once exclaimed (with joy and anxiety), “the rhythm is gonna get’cha.”

The Colombo Event, when it comes, will be far less an event as exalted by Accelerationism than an ongoing crisis, a daily grind, that cannot be accelerated away from by breaking through the ongoing and cyclical process—it is life itself and the discordance between the elements spill onto a body. These are the flows of world historical and quotidian anguish that Kamau Brathwaite expresses in defining “tidalectics.”“tidalectics.”Stefanie Hessler (ed), Tidalectics Imagining an Oceanic Worldview through Art and Science, (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2018). The event is as much about how time flows through a place as it is about a place in time.

Colombo families gather on the circular terrace of the temple adjacent to the port and linger there to observe the changes that accrue. They’ve been coming here for years, and now they take the time to study the rapid transformation brought about by the CCCC (China Communication Construction Company), then tweet about the frantic transformation at a distinct but no less frantic pace. The ongoing and cyclical polyrhythmic discomfort here is less a question of what to do about a single oppressive rhythm, but how does one distinguish a mistake in rhythm, which leads to the eradication of distance and difference and a break in circadian and circa tidal flows?

Circadian and circatidal rhythms give humans, and other-than-human beings, some clarity over their positions in time and their relationship to space. The loss of circadian rhythm is, then, a loss of home—not as a territory with a physical address per se, though this is often true as well, but as a perceptual geography that makes it possible to become unhomed, “home-less” rather than merely “unhoused.”

The tides will rise. Time, as always, can wait

In “Of the Refrain,”“Of the Refrain,”Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987), 310-351. Deleuze and Guattari explore such loss as a function of the fragility of a territory: “a mistake in speed, rhythm, or harmony would be catastrophic because it would bring back the forces of chaos, destroying both creator and creation.” As rhythms collide in Colombo, one can feel new fragilities being inscribed in the creators of the new port and their creation. The tides will rise. Time, as always, can wait.

Stiegler writes that while industrial progress most often outpaced cultural progress, it has always been contained within the realms of what human bodies can collectively evolve to accept. As the flow of the cognitive factory outpaced the industrial infrastructure required to support it, we’ve become dividuals capable of assimilating progress in certain parts of the organism but not others. We wait, sometimes unconsciously, for a future which parts of us already live in.

10.000 Things Out of China follows the flow of selected household commodities as they move between logistical chokepoints before and after their purchase by consumers. The work that began in 2016 as a relatively simple “one-line-trajectory,” turned into a cacophony of polyrhythmic flows between forced mobility environmental shifts, material commodities, and libidinal signposts.

The work stretched from Istanbul to Shanghai, Los Angeles, Pussan, Hong Kong, Athens, Colombo, Nairobi, Dubai, Singapore, Kampala, and it is a visual map of interlinked sites like Apple’s Foxconn iPhone manufacturing plant, the Penguin Printing Factory, Zara and Victoria’s Secret factories, Jebel Ali free port, CCCC, Cosco construction sites, and the offices of Harbour Engineering to name but a few. The project was financed by Abigail Cohen Fellowship and Magnum Foundation.

The great ephemeral skin of the sea has certainly evolved to accept the dominant rhythm of the Asia-America Gateway—generating and transmitting codes along its route, often to no discernible (no immediately perceptible) purpose. The message transmitted barely touches the skin, leaving a s/crawling sensation on the human port, in which a fragment of consciousness is uploaded into a cloud kept stationary in a digital sky by atomic oscillations.

This seems to me a process of gradual breaking down rather than breaking through, a conceptual scaffolding for forming the Accelerationist movement of the 90s—borrowed from Deleuze and Guattari via R. D. Laing. The power of existent rhythmic regimes lies not so much in simple acceleration and speed, to be subsumed by further acceleration, but in the uniformity of speed (an imposed loss of rhythm) at which transcoding occurs between one milieu and another. Accelerationism’s “speed cure” is arhythmia’s disease.

This, in turn, makes any agenda for deccelerationism, for a strategic withdrawal, or the formation of islands of escape, expressive of a barren notion of a utopia. Indeed, to speak of this “utopia” is itself a kind of arrhythmia; “utopias”' are the only possible utopia. The ideorrhythmyideorrhythmyRoland Barthes, How to Live Together in Everyday Spaces - Robinson Crusoe, Idiorrhythmy, (Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 2002 [1977]). will define the tempo of any utopia.

Writing out the utopia of ideorrhythm through the history of monasticism, Barthes aptly articulated a difference between the communities subjected to the (singular) rhythm of power, those that constrained themselves by strict schedules, defined by common regulations of overall rhythms that they neither chose nor opposed, a kind of passive inscription of social Taylorism. These contrast with communities or individuals who choose to live by their own rhythms communally, collectively, and at a social distance to the forms of life that suffocate singularity, the “different drummers” heard by Thoreau’s primitive anarchist. But this is a position that leans on the established boundaries between work and rest, subjects and sovereigns, institutions and individuals. In Barthes’ world, there is someone one may, at least implicitly, refuse and resist; yet in this age, sovereignty is elusive, as each individual assimilates the leading rhythms internally, and, even then, only in part.

For Adorno, likewise, the rhythm of powerrhythm of powerTheodor W. Adorno, Minima Moralia (Berlin: Suhrkamp Verlag, 1951), 53-58. was an alternation of frenetic action and the total boredom of standstill, a byproduct of the lack of geographically attainable enemies. Adorno’s view may suffer somewhat from a radical materialism, and a proximity to psychologies of conflict, but in the current polyrhythmic network, enemies are never at a distance, (nor is boredom), and all distances are only a second away. Geography itself is, in turn, never a static backdrop, but an endangered—and endangering—territory where neither fight nor flight reduces sufficiently the suffocating sense of perceived precarity.

The paths of objects across the borders of the polyrhythmic network narrates the story of a body in absence, lost, reconfigured, or stretched along industrial flows and fluxes. Ports, packing houses, and factories are written by numbers as distinct space-time-continuums. Follow the numbers and you may not know where or when one ends and the other begins.

The Victoria’s Secret and Zara textile pattern manufacturing factories have the air of a hospice about them. The industrial town of Humen, near Shenzhen, smells of dyes and textile detritus. The town is eerily silent. This town, dedicated to the industrial production of textiles, is now almost completely abandoned. Walking in the town, it is not immediately clear by whom, or where, or under which conditions, the textiles are produced.

Still, the factory exists and the containers arrive and leave on time. “Chinese magic,” the director explains, pointing at the computer screen, then saying, only in passing, that he subcontracts the orders subcontracted to him further along a supply chain split ten ways. His facility is so far down the line that he seems to neither know nor care who he manages, or who is managing him, an anonymous sovereign to anonymous bodies in a labyrinthine hellscape of self-surveilled labor.

Apple’s Foxconn complex on the other hand, is a grid broken into even blocks: A, B, C, D, E, and F. Here the internal transport system that moves the commodities also moves the bodies of the workers, their managers, and the internal police force, in a single sweep. Traffic peaks from 6 to 7AM, and then again from 4 to 5PM, when three orderly waves move work groups on and off shift. The next, shorter wave, flows in at midnight.

Local drama unfolds slowly between the shifts, in the shaded parks where the workers, left to their own devices, text to the person next to them rather than speak. They scroll through timelines in search of the ever-elusive object of desire, or desire itself. Their bodies, physically still, subvert the institutional rhythm. The approved Foxconn Body is perpetually dynamic, alternating between the monotony of physical labor and the boredom of the internet. The devices, much loathed by the people producing them, are advertised and sold at a discount within the complex, along shops in internal side lanes.

The fatal leaps that continue to occur from Foxconn roofs with unsettling regularity are not so much a protest against the rhythm of power or the working conditions—but a leap of exhaustion from the invasive sense of restlessness in its totality.

Foxconn’s traditional institutional response to mass suicide was to restrict the flight of the body from a roof by nets, and, when that proved ineffective, to impose strict leisure rhythms by redirecting the bodies of workers towards free counselling sessions, a swimming pool, and a spacious running court, all, for the most part, left empty. The rhythms of rest and labor now fully dissolved.

“A factory is still a factory,” an educated engineer tells me when I ask him about the suicides, and why the improvement of the working conditions made no difference, “And there is nothing else.” By nothing else, we clarify through considerable efforts on the part of the translator, that he means an exhaustion of any aspiration that would serve as an internal coping mechanism, creating windows of possibility for escape. Hope’s ebb tide. This final act is then directed at much, much more than just the Foxconn management.Foxconn management.Anyone still under the impression that Chinese labor practices stem from a radically different ideology than those of its Western competitors may want to consider the Van Nelle coffee/tobacco factory. Which could double as a museum of labour relations, with its iconic ramps for moving stuff in and out. The staircase was designed to separate the genders from meeting, keeping reproductive bodies apart between shifts of productivity. Special thanks to Professor Clemens Driessen of Wageningen University for introducing me to this conceptual factory located in Rotterdam, Netherlands. It is existential in the most fundamental sense, concerned with the nature of reality and our capacity to intervene, to feel time as a block pressing one into the void rather than a dynamic flow meandering adventitiously. Chance is exorcised by the unseeing clericy of the market.

“Saying no” is the only utopia we can conceive of today. Well, “No!”

A container ship, on the other hand, is a mobile node on the surface of the network, a floating institution that contains within itself each polyrhythm and its distinct tensions. As soon as land disappears from view, the ship, much like the immobile monolith of Foxconn, imposes a steady rhythmic signature. A fixed circadian system that matches the oscillating physical environment marked by the rituals of work and rest spaced at even intervals of four hours; a maritime equivalent of an industrial techno beat. Letting go of the individual rhythm of a body while assimilating collective and institutional and maritime habits, however difficult, is a way of producing a temporary home inside a moving institution, at sea. Here the rhythm of the waves and of sovereign power, despite its brute regularity, offers a glimpse of respite from the contemporary onslaught of stimuli on land. There is a clear sense of the end of a day, that everything that could have been done has been. In some ways, the ocean is where the memory of pre-historic rhythms can be most directly felt with its radically different biophysical rhythms. Life at sea, inside the containership, is both a prison and escape from prison, a kind of commodity-based monasticism.

New CCCC highway construction running between Kampala city and Kampala airport in Uganda

Port City construction by the CCCC in Colombo, Sri Lanka

Air conditioners discarded at Foxconn, at a rate of 20 to 30 per day

Hong Kong Alt-logistics centre

Port Authority Office, Port Klang, Malaysia

Shenzhen textile factory neighbourhood

Port of Jebel Ali in Dubai

Mombasa, Nairobi Railway, CCCC construction site

Port of Shanghai

Serpentine Road in the Port of Hong Kong running between the cargo ships and land, delivering tracks with new materials and commodities and taking the garbage back up onto land to be transited further into China

Serpentine Road in the Port of Hong Kong running between the cargo ships and land, delivering tracks with new materials and commodities and taking the garbage back up onto land to be transited further into China

Maintenance station aboard a German-run Malta-owned container ship said to be made in China out of broken bicycles

Maintenance station aboard a German-run Malta-owned container ship said to be made in China out of broken bicycles

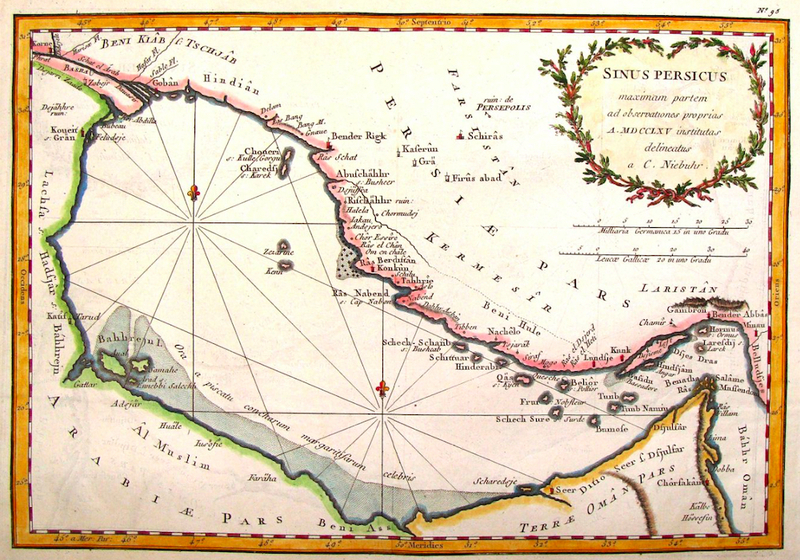

Waiting for the pirates in the Gulf of Aden

Suez Canal on the left

Suez Canal on the right

South East China Sea, in spring

Chinese state authorities on an official visit to the Port of LA, California during the inauguration of Donald J. Trump

Hong-Kong stock market, trading floor

Within this territory mapped by objects and connected by nodes, it is rather difficult to contemplate the means of resistance through politics of escape. The reluctance to part with such a utopia has less to do with its value than with a perceived lack of alternative. Or, as China Mieville points out, echoing Herman Melville’s Bartleby the Scrivener, “saying no”“saying no”“We need utopia, but to try to think utopia, in this world, without rage, without fury, is an indulgence we can’t afford. In the face of what is done, we cannot think utopia without hate.” Because hate is not capitalism? Or a marketable identity? For less militant theories of deccelerationism consider: Peter Pal Pelbart, The Cartography of Exhaustion. (University of Minnesota Press: Univocal Publishing, 2013). Also, Mehdi Belhaj Kacem and Peer Illner, “An Invitation to Contribute — A Conversation about Unworking” in Continent, issue 6/2, 2017; as well as recent “Bifo” Berardi though in his latest work he sounds too scared for a reader to follow. is the only utopia we can conceive of today. Well, “No!”

Deccelerationism, deliberate inoperability, occlusion, and infinite resignation as a form of political protest against the current rhythmic tension offer welcome ripostes to Accelerationists’ morbid fascination with disaster capitalism, and at times a kind of food for thought, but the window of respite is brief at best. And, as the temporal boundaries between those producing ideas and those forced to inhabit them grow ever thinner, the figurative and actual acts of inoperability can no longer be abstracted away from the production of the conditions that allow for multiple interpretation of what constitutes the inoperable. As it stands, reading of such neg-utopias on broken phone screens during smoke breaks under the rhythmic constraints of dominating rhythms does not, at present, allow for more than just one interpretation. Whether such interpretation is intended or not is beside the point, as the value of utopias rests on the ability to multiply the conditions necessary for thriving, however imaginary, not in diminishing them.

In How to Do NothingHow to Do NothingJenny Odell, How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy (New York: Melville House Publishing, 2019). To be fair, Odell’s book, categorized as self-help, has succeeded at convincing large swathes of US readers to consider that maybe working ourselves to death isn’t anything to brag about. So it is certainly a great and perhaps unavoidable starting point for the path I'm trying to map out here. Jenny Odell urges the reader to pay attention to various things: art on museum walls, birds, nature more generally, and to create distance from the miserable barrage of opinions on the internet as forms of resistance to the demands placed on our being by the “attention economy.” As tempted as we understandably may be to follow Odell into the (mythical) higher world of the “not online,” the dream-bubble of an island community where individual rhythms can co-exist collectively at a distance bursts before it can form. The artworks at the museum were not made from a separate cloth, eco-rhythms are affected by the industrial flows in more ways than we are able to decipher, let alone control.

The act of paying sustained attention alone does not make all things equally nourishing, and, if it does, then that same logic can certainly be extended to the mass cultural production, placed low on the hierarchy of “worthwhile” things by the author. Jennifer Garbys’ Programme Earth and Citizen Sense projects take an Odellean notion of attention and seek to activate it, but the capacity to cultivate forms of awareness and even create new forms of data production, collection, and organization that would only achieve an objective of the project through scale acquired in good time.

Seeking distance in the illusory binary between productivity and inactivity, inside and outside, on and offline, between over-saturating sociality of capital cities and the extreme isolation of silent retreats, between offline nature and algorithmically-driven culture is a gesture in the direction of an aspirational self, an individual success (a seductive diversion Garbys’ model is quite susceptible to); it formalises a utopia that is dependent on competition for resources, the resource of time if nothing else, a separation from others perceived as threats, and the surgical severing of the parts of ourselves that have already internalized the rhythm of 2.88 terabits per second.

The everyday gestures that decide if an encounter will become a relationship, who we stay with, who we follow

Still utopias, plural, are indispensable in reconciling these proliferating polyrhythmic tensions, and for producing temporal domains without enemies. In the process of envisioning utopias, we always-already create modes of sensorial perception that enunciate rhythms, recognize and separate them. The question of rhythm and form defines this production, not the process of simply mirroring reality in opposition to it. Fiction often works to reconfigure space, inventing abstract streets suited to experience, but, along the way, it produces a framework in which rhythms can be (re)imagined, (re)captured, and (re)altered; a perceptual geography defined within temporal parameters, a mobile transit zone where what matters can be reconfigured, suspended, or extracted before reentering or disappearing from the swirling circuits.

To begin this game without withdrawing, amid the chaos of a sensory ocean of detached stimuli, beyond rest, we have to believe not only that the exercise is necessary, but that it is easy. We must believe this precisely because it’s not easy. This conceptual step is often skipped, but it’s an inevitable precursor for any grand or small vision of eco-industrio-socio-rhythmic harmony. By “easy,” however, I certainly don’t mean the cruel optimism of smiling in the face of calamity, but careful, micro-gestures of potentiality already afforded to all of us by existing interfaces with minimal reconfiguration, a crack, where, in the much quoted Leonard Cohen lyric, “the light gets in.”“the light gets in.”“Ring the bells that still can ring.

Forget your perfect offering.

There is a crack, a crack in everything;

That’s how the light gets in.” The everyday gestures that decide if an encounter will become a relationship, who we stay with, who we follow.

The temporary suspense of overbearing complexity, easy beginnings, is, in itself, a project of recognizing power in withholding immediacy, embodying it, not escaping it, in judging events according to their potentiality for becoming. This is where the superficial, the surface, the mattering, imperfect form, can allow for a glimpse into the other-than-human rhythms elusive to strict definitions (e.g. human, machine, digital, analogue) and beyond false binaries (virtual-real). The nodes, where perpetual anticipation of conflict can be suspended. The interface as the proverbial pendulum? The Cosmic Hammock? Swings and Roundabouts? The iPhone in 4/4? Even the minor alteration to the interfaces may allow for a wholly non-agonistic encounter through change in the rhythm of transmission in all its multiplicity of meaning. A shared time-capsule in which the means of delivery is the beginning of the message.

* The contract for the construction of the Sri Lankan port of Colombo was signed between Chinese Harbour Engineering and the president of Sri Lanka, Maithripala Sirisena, in 2016 after years of negotiation. Traces of paperwork around the deal date back to March 2007. In the 00s, the Chinese government assisted the Sri Lankan government in their war against the Tamil Tigers. By 2013, Sri Lanka was paying China US$30 million per year in interest alone for loans. In 2014, Chinese President Xi Jinping agreed to easier conditions in exchange for a 35-year-lease of Hambantota. In 2016, China Harbour Engineering and its state-controlled parent company had invested about US$12 billion for maritime construction projects abroad. It listed proposed bids and contracts not just for Hambantota, but also undertakings in Cameroon, Pakistan, Qatar, the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Angola, Nigeria, Singapore, Sudan, Vietnam, Cuba, and Kuwait.The Chinese portfolio is exceptionally diverse; it stretches across all continents and includes key assets in France, Malta, Morocco, Ivory Coast, South Korea, Pakistan, Singapore, Istanbul, Dubai, and many other countries including, of course, the US.