Archive of Regula Tschumi

Bottom left: Seth Kane Kwei in Teshie. Ghana Accra region, 1987

Roberta Bonetti / Kane Kwei family archive

Bottom right: Eric Adjetey Anang. Even the One Who Worked for It Is Dead, 2017

Collection of the artist / International Folk Art Market

In 1957, the Ghanaian carpenter Seth Kane Kwei was commissioned to make a ceremonial palanquinpalanquinType of human-powered transport, often taking the form of open chairs or beds carried by two or more carriers. in the shape of a cocoa pod for one of the local chiefs. Unfortunately, the chief unexpectedly died and the palanquin was changed into a coffin in which the man was eventually buried. When the carpenter's grandmother passed away not long after, he remembered her love for airplanes that often flew overhead and made an aircraft-shaped coffin. After the funeral, Kane Kwei started receiving tons of orders—this is how the appearance of the first fantasy coffins is described on the website of his still operating carpentry workshop, now managed by Eric Adjetey Anang—Seth Kane Kwei’s grandson.

The same story was retold by Western authors until the anthropologist Regula Tschumi, through her PhD research, disproved this popular version. According to her research, the Ga people’s chiefs had long been buried in figurative coffins that repeated the shape of their ceremonial palanquins, which in turn were made in the form of their kin’s symbols. This was due to the fact that the chiefs’ initiations and funerals complemented each other. Accordingly, various carpenters had made what would later be called “fantasy coffins”—prior to Kane Kwei.

Photography Roberta Bonetti

For example, Tschumi herself found the retired master Ataa Oko Addo, asked him to draw from memory something from his carpentry works of the past, and thus relaunched his career in a new direction—now as an artist. The researcher concludes that if Ataa Oko Addo made palanquins and coffins for chiefs back in the 1940s, then Kane Kwei did not invent a new form, but turned out to be one of those who democratized it: what used to be a part of the rituals of the elite became available to a broader circle.

Today coffins differ greatly. The owner of a taxi company, or at least one taxi, can be buried in a car-shaped coffin, a shoemaker—in a giant sneaker, a fisherman—in a fish or boat. One can only guess who the coffin in the form of a mobile phone was intended for and who was given a coffin shaped like a can or a bottle of popular soft drink. The shape of the coffin is supposed to either speak to what the deceased was famous for or reflect his or her character traits: the meaning of lion- or eagle-shaped coffins are probably obvious.

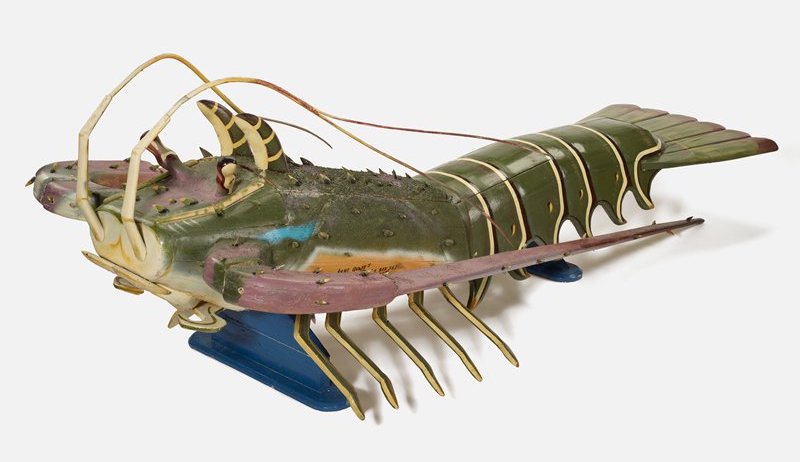

Sennah Sylvester. Coffin in the shape of a lobster, 2000

M 2011/25, Museum für Sepulkralkultur

Paa Joe and Jacob Tetteh-Ashong. Coffin in the shape of a Walkman player, 2015

Art Twenty One

Eric Adjetey Anang. Coffin in the shape of a shoe, 2017

Collection of the artist / International Folk Art Market

Samuel Narh Nartey. Coffin in the shape of a Nokia cell phone, 2007

2009-3-1 / Smithsonian National Museum of African Art

Paa Joe. Coffin in the shape of a Nike trainer, 2015

Gallery IFAC Arts

Sowah Kwei. Coffin in the shape of a lobster, 1993

2010.72, Minneapolis Institute of Art

Paa Joe. Coffin in the shape of the Fort Gross Friedricksburg, 2004-2005

Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

Seth Kane Kwei. Coffin in the shape of a cocoa pod, circa 1970

Randy Dodson / Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Paa Joe. Coffin in the shape of an elephant, late 20th century

2010-9-1 / Smithsonian National Museum of African Art

Paa Joe. Coffin in the shape of a red fish, 2004

Ruttkowski;68 / Artsy

Paa Joe. Coffin in the shape of an Air Jordan sneaker, 2016

Ruttkowski;68 / Artsy

Unkown artist. Coffins in the shapes of a camera and a cell phone, 2002

Roberta Bonetti

By the 1970s, fantasy coffins not only had gained popularity in the neighboring cities of Teshie, Nungua, and Labadi, where they by then had become a part of the modern burial culture of the Ga people, but also started to draw the attention of Western collectors. In 1989, Kane Kwei’s and his nephew and former apprentice Paa Joe’s works appeared at the Magiciens de la terre exhibition at Centre Pompidou and La Grande Halle de la Villette. Its curator Jean-Hubert Martin collected the works of fifty African and fifty Western artists, and since then, fantasy coffins have become part of the African art export market. They are ordered by both private collectors and museums and exhibition spaces.

Moreover, as noted by another researcher Roberta Bonetti, Western perceptions and international museums also affect the context for manufacturers. Firstly, coffins are turned from utilitarian ritual objects into art objects, and their authors go, from artisans—to artists (which at the same time has caused art criticism debates). Secondly, the Western gaze chooses what looks the weirdest, brightest, and characteristic: it is not coffins shaped like lions and cocoa beans, but those that reproduce the products of international brands from Nike and Nokia to Coca-Cola. While in the domestic market, the demand for coffins-telephones is still inferior to the demand for the fauna and flora of genesis and individual symbols.

Be that as it may, the most successful workshops seek to benefit from growing international recognition. And it is not only related to galleries and museums commissions—the already mentioned Eric Adjetey Anang is consistently turning the name of his grandfather Kane Kwei into a brand, noting that the use of the workshop’s website and the Wikipedia article has brought numerous tourists to his workshop . Thus, it has ceased to be a place only for the provision of ritual services and the production of art objects and has gradually turned into an exhibition space instead.

As the culminating point in this intricate mix of rituals, crafts, art, and market there stands a 1.5-minute video starring Eric Adjetey Anang, where a story of Kane Kwei’s workshop and fantasy coffins ends up as an advertising campaign for a drink produced by the Spanish division of Coca-Cola. The advertising agency dug deep enough to build a concept around the Ghanaian name for the fantasy coffins—“abebuu adekai,” which means “receptacles of proverbs.” Kane Kwei’s workshop made two coffins shaped like a can of this drink, one of which, as part of the campaign, collected the dreams of Spanish buyers. The circle was closed: the reproduction of brands attracted a new brand, exotisation and commodification unfolded at the meta-level; “receptacles of proverbs” turned into a box of fairy tales.

Translated from Russian by Olga Bubich